The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

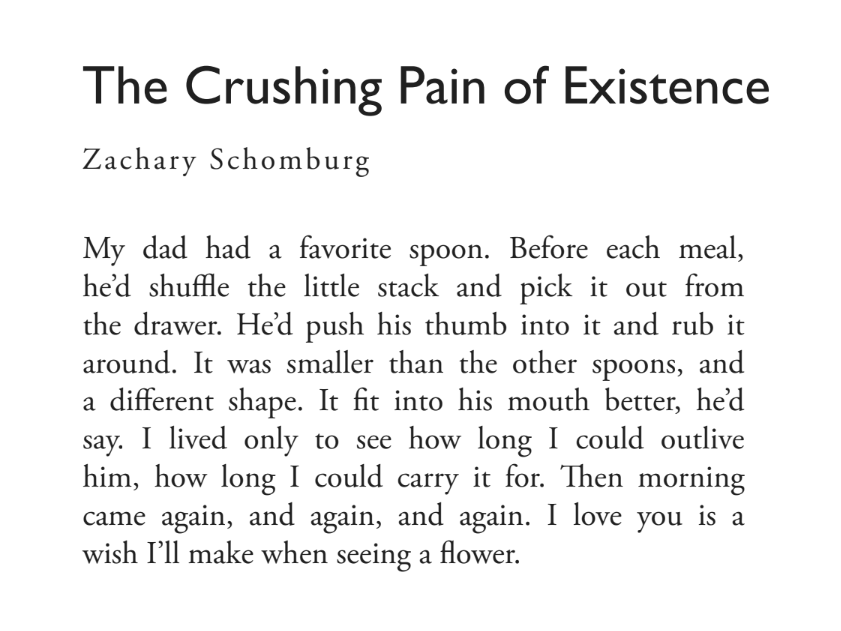

This week, editor Maddie Woda discusses “The Crushing Pain of Existence.”

Zachary Schomburg’s “The Crushing Pain of Existence” simultaneously makes me want to sigh with contentment and furiously weep, two excellent emotions to invoke in tandem. While I’m hesitant to throw the word “bittersweet” around lightly, this poem sits squarely in what I have to call a bittersweet tradition, in company with Liesel Mueller’s “Late Hours” and Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones.” The language in “The Crushing Pain of Existence” is refreshingly simple, stripped of phrases my granddad would call “highfalutin” in his mild Appalachian accent. It is not stripped of sentiment, and this mild gooeyness might repel some readers–how many of us in poetry think we are post-sentiment, post-earnestness?–but I invite readers to lean into the sentimentality.

My roommate’s long-distance boyfriend visited her at Columbia for the first time last year. After dinner, he plonked down in the nearest armchair, ready for conversation. My three other roommates and I froze. “Babe,” my roommate nudged, “You know how your dad has a chair and everyone in your family avoids sitting in it? You’re sitting in Maddie’s chair.” How many of us have experienced something similar, whether a roommate’s chosen chair or a mug from which only your mother drinks her coffee? We anchor our lives in these small traditions. The first part of Schomburg’s poem outlines this specific phenomenon, its simple resonance. The child in the poem distills her father’s personality into this quirk, but it contains volumes about their relationship. My mind springs in all directions: he was home frequently enough to have a favorite spoon; perhaps each Sunday evening they ate ice cream together on the porch, father and child. He is a particular man but not fussy, a carpenter maybe, someone who measures and aligns. He favors touch of the five senses, his thumb imprinted on the cool metal of the spoon. Maybe the spoon was in his grandmother’s silverware set, the last of the tarnished silver to get passed down. It is a symbol rife with meaning, but it is simple in its delivery of the symbol. It is the reader who imbues it with meaning, sentimental as that may be.

And then, of course, the volta-like shift, “I lived only to see how long I could outlive him.” In a few words, the poem evokes the melancholy of loving a parent. You are expected to live life without them at some point, whether because of death or distance. Their personal traditions, which spoons they use for soup, are no longer acquired knowledge, no longer as obvious to you as the shirt they wear on Sundays. The last line is the most sentimental of the bunch, admittedly, but it saves itself from being cloying by shape-shifting. Every time I read it, it evolves into a new meaning. The flower is transient, but recurring? Its winter death is a part of life, its resurrection each spring equally expected? Somehow, it captures the tension I have always felt by being close with my parents. It is love with an expiration date: painful if they go first, tragic if I go first. It is wrapped up in responsibility, shame, devotion. I am a distorted reflection of them, and our love for one another is a wish.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.