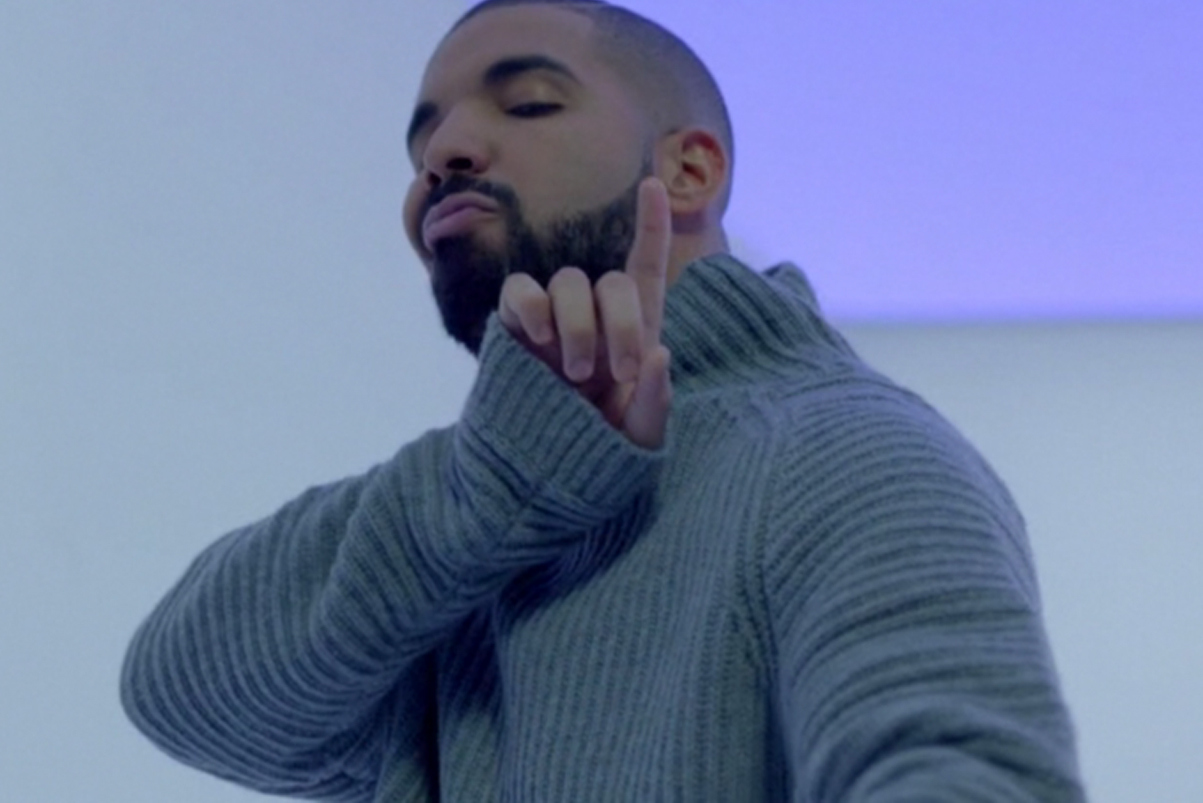

Recently, a BuzzFeed article entitled “47 Drake Lyrics For When You Need an Instagram Caption” has been surfacing frequently on my Facebook News Feed along with hilarious new dubbings of Drake’s now famous “Hotline Bling” music video. Although I often use Aubrey Graham’s lyrics in my Instagram captions to convey emotions ranging from solipsistic self-confidence to romantic woe, I did not bother reading it. I assumed that I knew all the lyrics already, and had perchance even used a few myself. It was not until my friend and colleague, whose opinion I greatly respect, had posted the article directly onto my Timeline that I decided to give it my attention.

The article places quotes from Aubrey Graham into general categories, including “For the Squad and Bae” and “For #blessed.” As I scrolled I nodded along, even envisioning some potential quote-photo pairings of my own. A significant portion of Drake’s ever-growing corpus, however, was missing. In “Headlines,” off his sophomore album Take Care, Drake, whose earlier work consists mainly of very relatable moaning about various women, proclaims: “Money over everything, money on my mind.” Such materialistic statements have only become more common as his career has progressed from Nothing Was The Same onward: “All I care about is money and the city that I’m from” on DJ Khaled’s “I’m On One” or “Hard to make a song about something other than the money” on Nicki Minaj’s “Truffle Butter.” To be clear, I am not in anyway suggesting that these lines should be included in a list of suitable Instagram captions. I am merely claiming that it is about time that we look at Drake as more than a generator of witty one-liners and reflections on the ephemera of millennials as depicted on social media.

Just over a year ago, comedian John Oliver discussed the relevance of Ayn Rand and her works in modern society on his HBO show Last Week Tonight, in a segment called “How is this Still a Thing?” Towards the end of the segment, the narrator humorously suggested that conservatives could chose “so many other advocates for selfishness,” citing Drake as an example. But how humorous of a suggestion is that? If Beyonce has become a popularizer of feminism, why can’t Drake assume a similar stature? How is Drake not the perfect popularizer, if not spokesperson, for capitalism in modern pop culture? Why shouldn’t he, rather than Rand, be the patron saint of moneymakers?

Speaking from a purely aesthetic standpoint, Drake is, first and foremost, significantly more palatable than Ayn Rand. Many conservative politicians have claimed that they read The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged frequently, almost as religious texts, and Rand does have a sizeable following in the general public. But Drake, to take the artist’s own words, “does numbers like its pop.” In October of 2014, he surpassed the Beatles, arguably one of the most popular musical groups in all of pop music history, in the number of songs on the Billboard Hot 100 and, in February of 2015, tied with them in the number of singles simultaneously on the Billboard Hot 100. The number of people willing to read the insufferable behemoths of Rand’s corpus would pale in comparison to the sheer mass of people buying Drake’s music or the Drake presale code for his upcoming tour.

Yet, in terms of artistry and ideology, the two often have very significant overlap. Some of the greatest odes to greed and materialistic gain that Drake has produced up this point, such as “0 to 100/The Catch-Up” and “10 Bands,” are imbued with a perpetual motion, both in terms of lyrics and production. The central metaphor of “0 to 100/The Catch-Up”‘ is the Canadian equivalent of accelerating 0 to 60 miles per hour, while the stripped down beat of the first half of the song constantly surges forward in powerful bursts. This is analogous to the symbolic role of trains and railroads in Atlas Shrugged, where individuals, through the power of their wills, overcome the stifling effects of collectivization. In “10 Bands,” the listener gets a very detailed description of Drake in his process of artistic creation: “I been in the crib with phones off/I been at the house taking no calls…I’m still awake, I gotta shine this year.” This infectious rhythm and energy propels the listener further than Rand’s convoluted yet blunt prose ever could.

Beyond his similarities to Rand, the singer-rapper’s work deals with a number of other concerns of modern capitalism. The most recent controversy surrounding Drake was the subject of a very public feud with Philadelphia rapper Meek Mill: the authorship of his songs. Drake has since admitted that he is ”ashamed” for working with ”individuals to spark an idea.” But Steve Jobs, another great capitalist icon, used software and hardware created by others for his artistic creation, rarely giving them credit either. Just as Jobs never truly felt the need to acknowledge the contributions of, for example, Steve Wozniak, Drake not admit to receiving help on any of his songs from, for example, Quentin Miller until the leaks of Miller rapping became available to the public. It is essential in most industries to find success through a combination of self-centered individualism and the exploitation of others’ ideas. Aubrey Graham fits right along with the other champions of capitalism.

So what does Drake’s work say about the state of modern capitalism? In an interview with Jian Ghomeshi for CBC, Drake revealed two key features of music: he solely composes in minor, and he composes his music for the exclusive purpose of nighttime driving. Due to the traditional associations of minor keys with sadness, one could almost immediately read an underlying sense of tragedy in Drake’s work. In “Plastic Bag,” off his mixtape with Future entitled What a Time to Be Alive, Drake tells a stripper at a club to “Get a plastic bag/Go ahead and pick up all the cash/Go ahead and pick up all the cash/You danced all night, you deserve it.” There is an unmistakable sadness in his voice as he tells this woman to perpetuate the system, which has so unfairly treated her, which has put her in this position. As for the nighttime driving, is Drake stating that capitalism is merely driving itself into the dark unknown, that behind the glory and outward splendor there is a lack of direction?

Even though these are largely speculative and very likely overly-romanticized conceptions of Drake and his body of work, let us no longer dismiss his music as merely a celebration of hedonism and self-glorification. Sure, replicate the “Hotline Bling” dance moves (keeping in mind all the time how problematic it is, as described in the BuzzFeed article “This Woman Just Wrote the Feminist Version of “Hotline Bling””). Sure, caption your Instagram posts with his impressive array of quotes. Who knows, it may even help you to get more followers due to the already big presence that Drake has on social media platforms. If this doesn’t work, maybe you should try to get free instagram followers so that you can get in contact with other Drake fans who will appreciate these types of posts. But consider the possibility that Drake’s work could reflect seriously upon the ways in which we live today. Consider the possibility that he could truly be a phenomenon of our generation that we cannot so easily dismiss.

List of links to referenced sources:

http://www.buzzfeed.com/michelleregna/thank-you-six-god#.er5Xm76wm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8m8cQI4DgM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTeZj19pAYE

http://www.buzzfeed.com/krystieyandoli/this-woman-just-wrote-the-feminist-version-of-hotline-bling

Venya Gushchin is a sophomore in Columbia College, and a member of the editorial board of The Columbia Review.