Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 novel A Little Life can be briefly summarized as the story of four college roommates, their enduring friendship and soaring careers, but it is so much more than a big-city Bildungsroman. About 100 pages in to the book’s 720, Jude St. Francis, the most reserved member of the group, recalls the first of his “episodes,” bouts of physical agony that continue for the rest of his life:

…the pain had been so awful—unbearable, almost, as if someone had reached in and grabbed his spine like a snake and was trying to loose it from its bundles of nerves by shaking it—that later, when the surgeon told him that an injury like his was an “insult” to the body, and one the body would never recover from completely, he had understood what the word meant and realized how correct and well-chosen it was.

Correct and well-chosen indeed; the novel slowly reveals the many torments Jude has suffered, from sexual slavery to being trained to self-harm by his childhood captor. They are torments from which he is never freed, the literal spine of a novel that is also an insult to the body of the reader due to the indelible mark it leaves behind.

A Little Life is grueling in its presentation of trauma. It is not a novel that can be passively read, and neither is it tragic catharsis, that purging of pity and fear imagined by Aristotle, for the feelings it creates never disappear. I first read itwhen I was sixteen, over the course of three days, neglecting all other responsibilities. Since then I have reread the novel several times, and my reactions to it are consistent: a headache and unsettled stomach, as if I’m seasick. My body recalls the memory of reading the book two years ago and replicates those feelings of captivated, visceral horror.

Critics were sharply divided on Yanagihara’s depictions of Jude’s suffering, the pages upon pages of ripped flesh and broken bodies. The New Yorker did not consider her rendering to be “excessive or sensationalist. It is not included for shock value or titillation…Jude’s suffering is so extensively documented because it is the foundation of his character.” Compare to the New York Review of Books, which considered the depictions “aesthetically gratuitous” and contributing to “a culture where victimhood has become a claim to status.” I think it is clear on which critic’s side I stand. There is something to be said for acknowledging a character’s pain without minimizing or beautifying it, and A Little Life does this unsparingly.

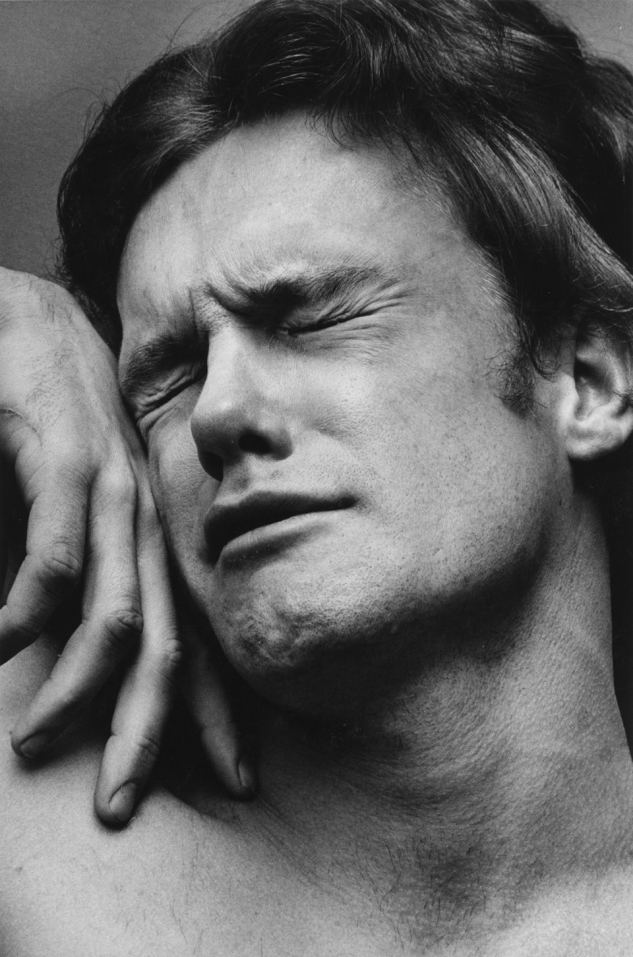

But I was recently confronted with something that forced me to reconsider my outlook on the presentation of Jude’s pain. This September, the International Theater Amsterdam debuted an adaptation of Yanagihara’s novel, over three and a half hours long and ruthless as the original text. During rehearsals, there was a video screen hung center stage to magnify Jude’s suffering, showcasing his intimate terrors and denying anyone the chance to look away. Close-ups of razors, of abusers’ predatory hands. The director, Ivo van Hove, and his colleagues cited this as a dramaturgical choice: for them, acknowledgement follows vision.

Though I stand by my agreement with the importance of acknowledging Jude’s pain, I would not have been able to go to this play. The thought of sitting down for four hours and witnessing those horrors—somewhat distanced in prose—brought to life makes me physically sick. There are things that are unbearable, and while for some the best way to bear them is to seethem, I know I would be incapable of watching Jude in the theater, or of sharing the witnessing of his pain with others. This does not mean that I think the adaptation should not have been made, nor that I am placing myself within the supposed “culture of victimhood” that the NYRB critic so scathingly denounced. For me, the best way to bear is to willingly remember in solitude, to accept the demands of memory as they resurface, to reread once more.

And yet, when I first finished A Little Life, I did seek the reflection of my experience in another reader, which I found in my then-English teacher. Meeting several times over the following months, we formed a kind of book club. We did not analyze Yanagihara’s free indirect discourse, the way her narrator slips in and out of minds and tenses like skins. We rarely mentioned Jude’s abuse. Rather, we talked about the passages that lingered in our memories, the moments of grace: Jude researching an autistic peer’s interests to help put them at ease during dinner party conversation, or Willem’s recollection of his favoriteOdyssey quote upon realizing that he has made a home with Jude.

He went to the kitchen to make himself coffee, and as he did, he whispered the lines back to himself, those lines he thought of whenever he was coming home, coming back to Greene Street after a long time away—“And tell me this: I must be absolutely sure. This place I’ve reached, is it truly Ithaca?”—as all around him, the apartment filled with light.

Perhaps abuse was only rarely mentioned because she felt it was an inappropriate topic to discuss with her student. Perhaps our understanding of each other’s feelings was implicit. Or perhaps we knew that our words as witnesses were ultimately inadequate. So we sat together and spoke of the light-filled moments, the burden of memory bearable for a time.

Spencer Grayson is a freshman in Columbia College studying English and Religion. Due to the current state of her wallet, her friends no longer allow her to enter bookstores unsupervised.