Editor (now alumna) Maddie Woda reviews Jihyun Yun’s first collection, Some Are Always Hungry.

In 2016, I stumbled upon Jihyun Yun’s poem “Recipe: Dak-dori-tang” in BOAAT. A freshman in Columbia’s English program, I was beginning to develop my taste for poetry. I liked narration, freshness, unapologetic earnestness. I did not want too much room for interpretation, worried I’d fall through the cracks and say something ridiculous in class. I preferred James Wright to John Ashbery. I could not name any poets who were not deceased white men.

I read “Recipe: Dak-dori-tang” and immediately fell in love with Yun’s style. While she didn’t spell out her meaning, she left me a net in her precise nouns: “goosed skin,” “tongue,” “sinew and ridged bone.” I hunted for more food poetry, “This Is Just to Say” and “Ode to the Onions,” and imagined they inspired Yun as much as they inspired me. I asked her to meet up with me for a cup of coffee, and she chose a shop with perfect mint iced tea.

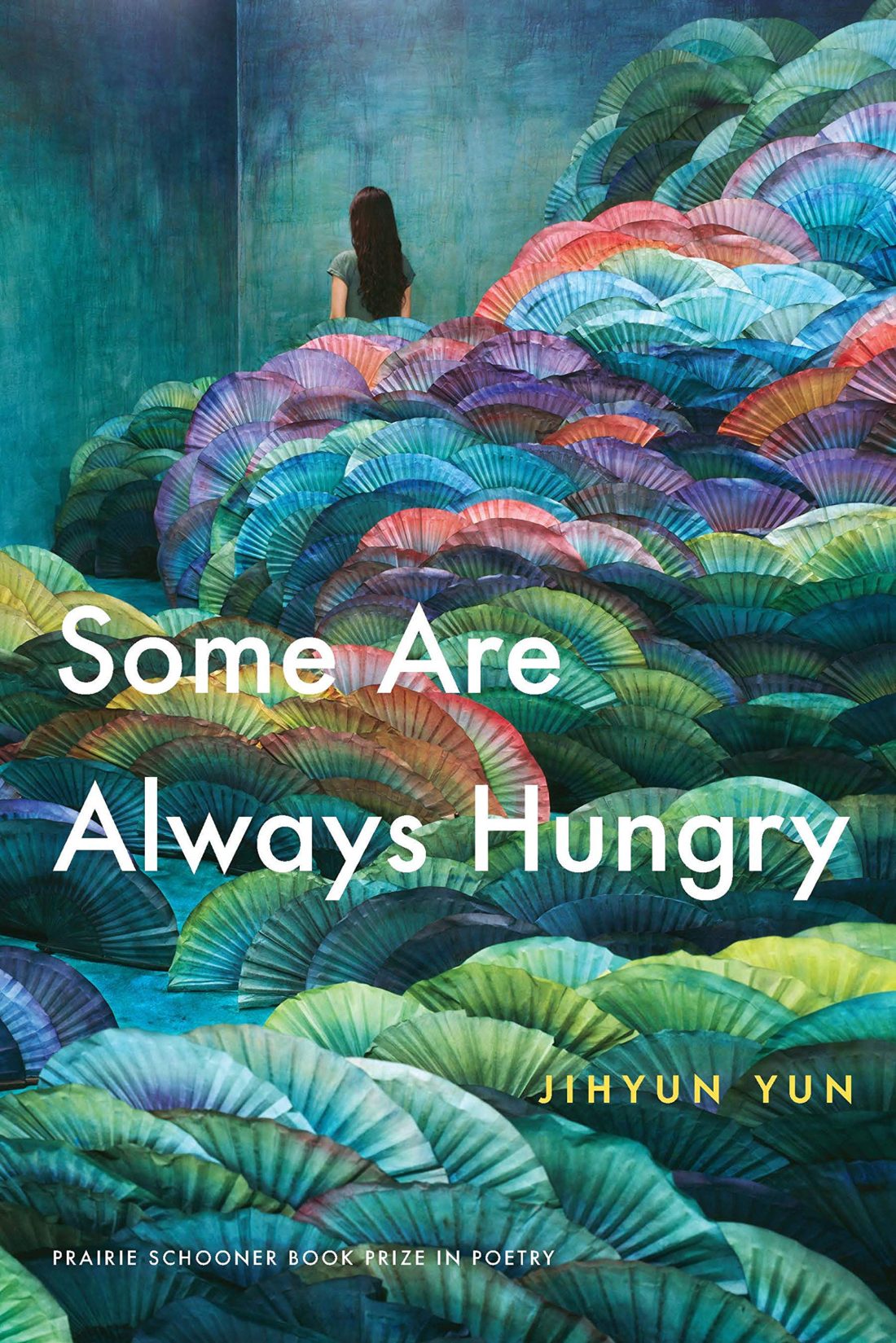

It is monumental then that I get to review Yun’s stunning first collection, Some Are Always Hungry. Winner of the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry, Some Are Always Hungry showcases what Yun does best. In honor of her “mother, & her mother, & hers,” Yun outlines a family history in recipes and literary diptychs, broad strokes and clacking teeth, the gutting of flesh both animal and human. She investigates generational trauma with a tenderness typically reserved for steeping tea.

Yun is known for her ability to seamlessly interrogate our consumption practices—what we eat and with whom, how culture and heritage color our dinner—alongside her exploration of womanhood: her own, her mother’s, her grandmother’s, and so on. The descriptions are graphic. The first poem, “All Female,” narrates her female family members cooking a meal of clams and crabs. She says, “my women crack them open, cleave the lip’s hem, plunge and snap.” Yun is not the first poet to draw parallels between violating an animal’s body for food and violating a woman’s body for pleasure, but in her poems, this metaphor reads as particularly searing. “Tell me again of love and its dark mirrors,” she writes in “Diptych of Girl in 1953”, a meditation on, presumably, her grandmother. “Well-skinned pear, our cheeks in the dust. The wet shred of a body.”

Food is the throughline that connects displacement, womanhood, family, and violence in Some Are Always Hungry. Despite hardship and degradation, a girl still has to eat, whether it be “zucchini cut to half moons” or “shucked-out sockets.” A girl, Yun’s grandmother or mother or Yun herself, still has to strive to be considered human amidst all the animals primed for consumption. I read the collection in one sitting, glutted with Yun’s piercing language, but I will always return for more. “Dear God of man’s waste,” Yun writes in “Lilith,” reading my mind, “I know I’ll leave this place hungry.”

Some Are Always Hungry / Jihyun Yun / University of Nebraska Press / $18 (Paperback)