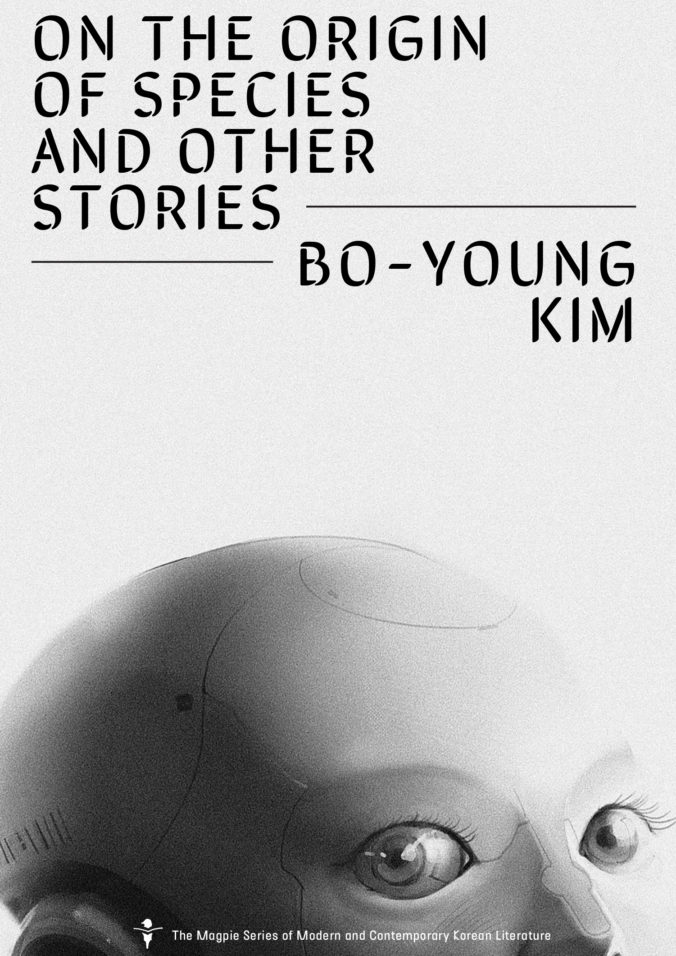

translated by Joungmin Lee Comfort & Sora Kim-Russell / Kaya Press, May 2021- $20 (Paperback)

You can be sure a collection of science fiction stories will be unique when it begins with “A Brief Reflection on Breasts”—Bo-Young Kim’s provocative forward to On the Origin of Species and Other Stories. The introduction hints at some of the stakes in the stories to come, stakes that explicitly involve questions of the body, society, existentialism, and human connection. To characterize the collection’s genre as simply science fiction would be misguided, since each story features an idiosyncratic blend of science fiction, fantasy, folklore, and philosophy.

Across the collection’s six short stories, readers find themselves questioning realities in an immersive video game, searching for wolves in a dragon-ruled land, and running from a maniacal king as a shape-shifting prince. Although their settings and characters differ widely, what can be found on each page is a commanding depiction of inner voice. Scruples, confusions, worries, and pleasures are so vividly rendered by Kim’s writing that readers will encounter no difficulty in finding themselves fully absorbed in each character’s dilemmas—no matter how far fetched they may be.

Through a video game representative’s attempts to figure out if players are human or AI, the collection’s first story, “Scripter,” offers a convincing argument that virtual worlds can be just as meaningful as real ones. Beyond a creative take on the Turing test, the story pairs philosophical questions of reality with issues of disability, loneliness, and empathy. Similarly, “Between Zero and One” refashions scientific concepts like time travel and quantum physics as tools to make sense of grief and suicide. In the collection’s title story, “On the Origins of Species,” an academically imaginative robot named Kay postulates the conceivability of organic matter, while constantly struggling to parse other robots’ social cues and facial expressions. Intermingling discourses of climate change, beauty, evolutionary theory, and emotion, the story stands out as a testament to Kim’s ability to connect vastly different domains of life and science.

I believe it fair to say that the collection has a preferred target audience. Familiarity with video game tropes, physics, and East-Asian folklore—among other disciplines—may not be necessary, but nevertheless helps with navigating the collection’s diverse contexts and concepts. But with or without the background knowledge, Bo-Young Kim’s stories assemble into an engaging response to pressing problems of existence and society that is both amusingly quirky and impressively mature.

— Sam Hyman

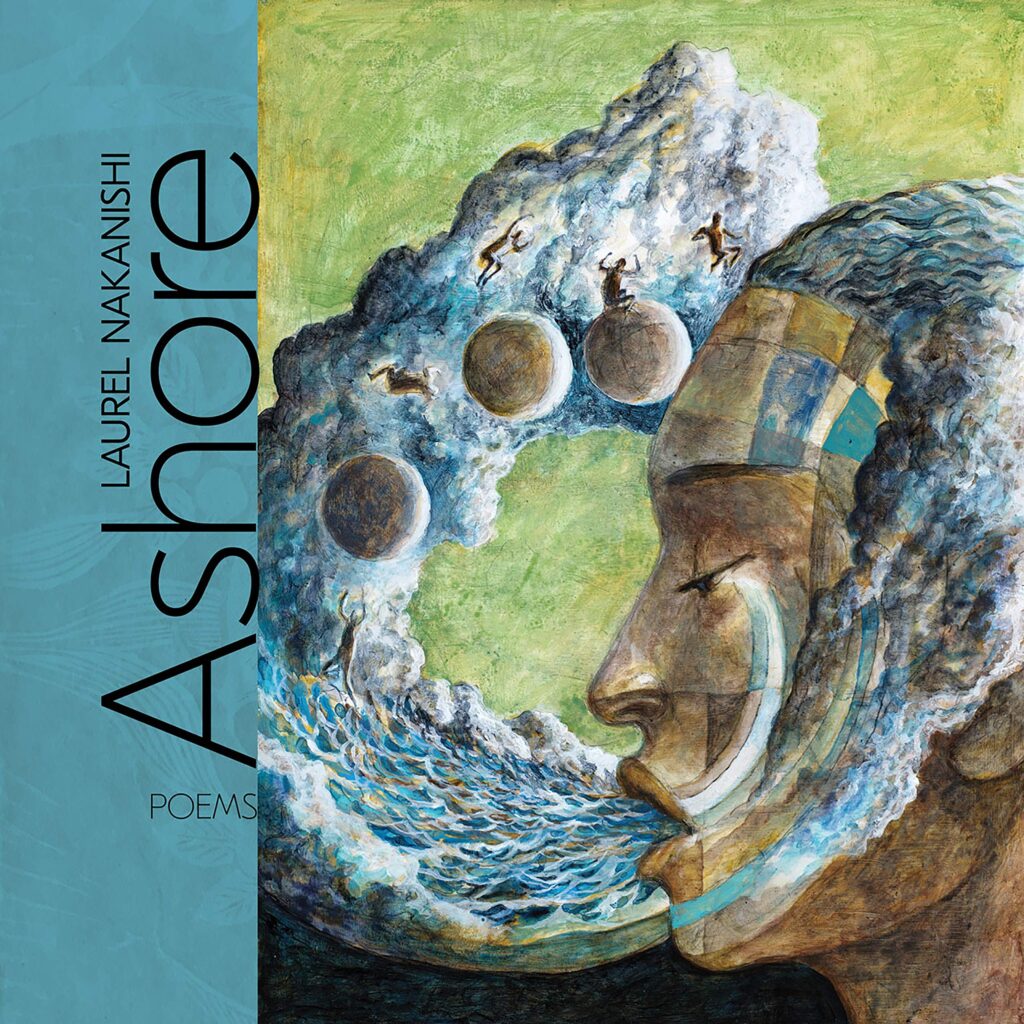

“We moved deeper in, farther away, tending the silences in our own feral minds.”

When Laurel Nakanishi writes this line early in Ashore, she writes a small guide for her poetry collection in the past tense. Her following poems circle into increasing detail; they see cultures, histories, and people separated; they care for what is hard to notice and wild. Ashore describes Hawai’i, where Nakanishi grew up and currently lives, its specific environments and cultural stories, and mixes these elements with Nakanishi’s family members, immigrant ancestors, and childhood memories.

Throughout Ashore, Nakanishi writes with care about nature and surroundings, never reducing them to simple subordinates or literary tools. Nakanishi writes to a bird and says, “You are not a metaphor / for a daring life among elements / You are not an element” (“Kolea, Pacific Golden Plover”). When she writes a catalog of animals encountered, humans come neither first nor last; they don’t stand out more than a black bear or a wolf. Nakanishi is noticing, and she plants details far enough apart to be appreciated whole, alone, on their own terms. When she writes about the Waimea Valley, Honolulu, or her grandmother, Nakanishi preserves the mysteries of incomplete meaning and incomplete knowledge. She asks; she prods; she says, “I don’t know what to wish / for her anymore.”

Maybe because Nakanishi writes with such humility and care, she writes searingly about what is not caring or humble: people damage the environment, exploit Hawai’i’s culture for tourism, and make people of mixed race, like Nakanishi, feel placeless. Nakanishi punctures expectations and rules out clichés. In her longest poem, she lists “forbidden words: aloha / paradise sun and sand,” and in another, she writes a poetic diptych, with one side a charming beach scene and the other an albatross split through with plastic, “leaking / bottle caps, lighters, ziplock / baggies.” Nakanishi is not blameless in these, either; she does not pretend she has not made the sea “full / of my own waste.”

In Ashore, Nakanishi writes so that readers see in alloy, where beautiful things and loving things are also damaged and hurt. Pieces echo and return to themselves, and continue echoing after Ashore ends. They act on the reader, while also being acted upon: influenced and not abandoning the specific world of ants, spiders, mountain ranges, and distant brothers. In her last poem, Nakanishi perhaps explains why she writes Ashore in her grounded, staying way: “There are stories at work in us / They hold us.”

— Wick Hallos

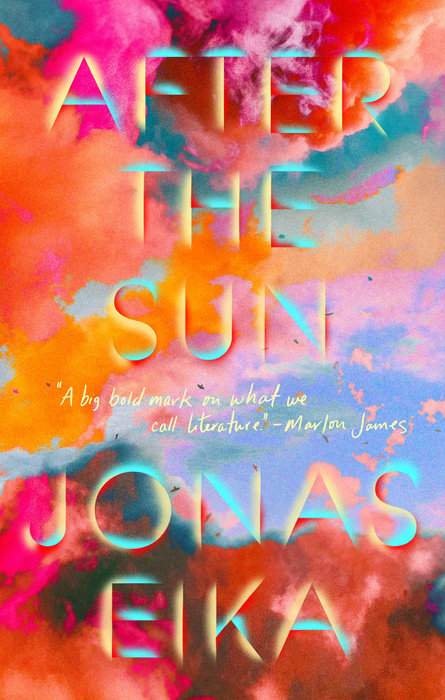

After the Sun / Jonas Eika, translated by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg / Riverhead Books, 08/2021 – $26 (Hardcover)

Jonas Eika’s award-winning book of stories – masterfully translated from Danish by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg – intertwines the corporeal and the fictitious across five intimate and brazenly surreal narratives. Subtly and openly, the psychosexual alienation and melancholic longing of Eika’s characters escapes the abstract confines of our contemporary moment to fill, quite literally, the tangible surfaces of throats, spines, eucalyptus soap, and empty shrimp shells.

The collection opens with “Alvin”, the story of an IT consultant who arrives in Copenhagen only to find that the building of his bank has collapsed into subterranean ruins. Upon ordering soup in a nearby café he runs into the eponymous Alvin, and the two plunge into a brief and hazy routine of derivative trading and sensually tinged showers. Homosexual desire similarly traverses “Bad Mexican Dog,” a narrative split into two parts that centers on a group of underage boys working in one of Cancún’s sandy beach resorts. The story’s sinister strangeness – on one occasion, the performance of a sexual ritual around the corpse of a beach boy triggers his resurrection from a pool of glowing colors – is reflected in the delicate prose of Eika’s third short piece. In “Rachel, Nevada,” a man named Antonio performs a tracheotomy on himself and incorporates part of a metallic object into his throat in a haunting and violent attempt to merge with the desert and its wildlife. “Me, Rory and Aurora” is the book’s arguably least surreal, but nonetheless grotesque, account of a homeless girl’s short-lived cohabitation with a struggling married couple in London’s outskirts.

Set around the globe, these stories rupture the fabric of the present with a force as incisive as the sun that engulfs them. Eika has crafted a book that is as much filled with lush light as it is changed by it.

— Panagiota Stoltidou