My greatest shame is that I own one song from a best-of-Willie-Nelson album. Don’t get me wrong — Willie Nelson is a lovely man, very talented. I don’t happen to know much of his music, aside from the single song I once heard on an easy-listening radio station in rural Maine. I’m not ashamed to own the song itself, per se. But I am ashamed of its membership in the best-of group, and its singular presence in my collection — a dual removal from its place in the original album and from the other songs of its apparent “best-of” caliber.

I’ve always believed that artworks belong in specific spaces. A song belongs in its album. You ruin it by clicking shuffle; you remove it from its natural habitat. A painting belongs in its frame, placed in the right part of the wall, lit from the right angle. A novel exists as a whole— don’t dare excerpt a chapter. It’ll wither and fade in an unfamiliar environment.

This impulse is tied, I suppose, to a confidence in artistic intention. If the artist presents this poem just so among these others, collection titled purposefully, ordered purposefully, even the cover artwork purposeful, who am I to remove it from its space?

This is why I’ve always bought full albums, never watched a T.V. series out of order, always read short story collections straight through. But recently I’ve begun to wonder if maybe I’m missing out.

This worry began when I found myself in the terrifying situation of being away from home with no books to read. I ransacked the shelves of my aunt’s house, finding legal textbooks interspersed with parenting manuals and Lean In-type corporate self-help books. Then, finally, I came across a dusty copy of The Best American Short Stories 2011, a collection of short fiction curated by the Australian author Geraldine Brooks. I was hesitant at first. Isn’t a best-of collection the same shameful concoction as my Willie Nelson album — a kind of shortcut for people who don’t want to sift through everything and find their own favorites? But I had no better option, so I sat down and read it.

Insofar as I read for a purpose, I separate literature from nonfiction in this way: I read literature as transportation and nonfiction as psychology. Short stories and novels are meant to lift me though some combination of sound and image and specific weirdness, to give me the giddy sensation of caring deeply for something or someone that does not exist. I think little about the author while I’m reading literature. If I consider him or her it’s not until later. And often I’m disappointed to think of the people who wrote books I love. I recently read an essay collection by my all-time favorite author, Ann Patchett. Her pieces are beautiful — thoughtful and quiet like her fiction — but I was uncomfortable thinking so much about the real personal experiences of a woman who wrote fictional scenes that feel so real to me. It was like coming down the stairs for a glass of water on Christmas Eve and seeing my mother putting presents under the tree — the feeling of being forced to confront the untruth of a manufactured experience.

Nonfiction, on the other hand — memoir, long-form journalism, and all the rest — I see more as a study of a mind. The subject matter of a piece counts less than the author’s analysis and presentation of it. I read nonfiction because I want to examine and inhabit the way another person sees the world. The draw, here, is almost the opposite of the attraction I feel to fiction; nonfiction finds its strength in the clear and necessary presence of a craftsman, someone whose intention and mind are aggressively visible rather than divinely absent.

When I found myself forced to resort to the best-of collection, I read it in a meandering way. I’d put it down and go eat lunch in the middle of a long story, returning to finish one piece and move on to the next. I decided that if I was going to consume pieces already torn from their natural place, I had no reason to read fluidly.

When I finished the book, though, I was satisfied in a confused, unfamiliar way with the collection as a whole. I had expected to experience that fiction-feeling — a removal from my immediate world. And I had felt that during each story. But layered over it I felt something like the authorial presence in a nonfiction piece; I could feel the editor of the collection, could sense her choices and taste. The collection drew as much power from her presence as a deliberate and unique editor is it did from the stories themselves.

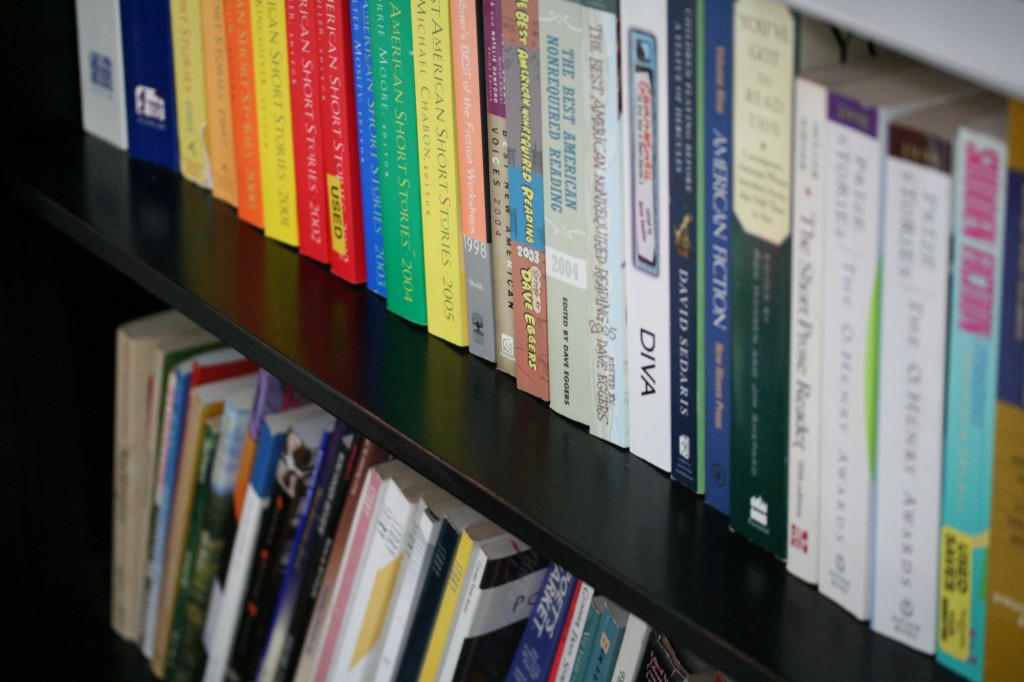

I’ve since read a few other editions of the Best American Short Stories and have discovered the thrilling if not unexpected fact that each one bears the mark of its editor as much as of the authors collected in it. The 2014 edition, edited by Jennifer Egan, might be my favorite yet — she shares my penchant for strange, sad stories. But the beauty of this format is that I could just as easily find a collection that represents the preferences of a romantic, cheery writer, or one who loves heavy-handed symbolism. I’ve realized that these collections don’t necessarily contain the best stories; who could judge that? Instead, they showcase the subjective preferences of interesting people.

Maybe I’m alone in my instinctual avoidance of art taken out of context, and in my impulse to avoid anthologies like these. The Best American Short Stories collections have been coming out since 1978 and show no sign of stopping anytime soon. I’m sure there’s a contingent out there who would laugh at my late appreciation. But to those like me who cringe at top-40 playlists and the Beatles’ 1 and yearly anthologies and themed collections and lists of the best photographs of such-and-such a place, I’ll say this: if someone put care into bringing these pieces together, if someone’s taste and quirks informed this collection, it’s probably worth reading. It’s two kinds of art in one, connected in a way I’ve yet to find anywhere else, and I can’t make any argument against that.

Charlotte Goddu is a first-year in Columbia College and a member of The Columbia Review’s editorial board.