Commencement season at Barnard College this year will mark the ninetieth anniversary of Zora Neale Hurston’s graduation with a BA in anthropology. As a graduate of Barnard’s sister institution, Columbia University, I feel the time is more than ripe to reflect on some of Hurston’s contributions. As it happens, I have a second—and third—connection to Hurston, apart from my status as a Columbia alumnus. Her hometown, Eatonville, Florida, lies not far from Gainesville, Florida, where I received my BA in anthropology.

I first encountered Hurston, in the company of fellow anthropology undergrads, at Eatonville’s annual “ZORA!” festival. Hurton’s literary and anthropological work was largely forgotten until 1975, when Alice Walker wrote an article in Ms. Magazine, “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” that revived interest in her writing. Without Walker’s persistence, we all would have lost one of the great writers and personalities of the twentieth century.

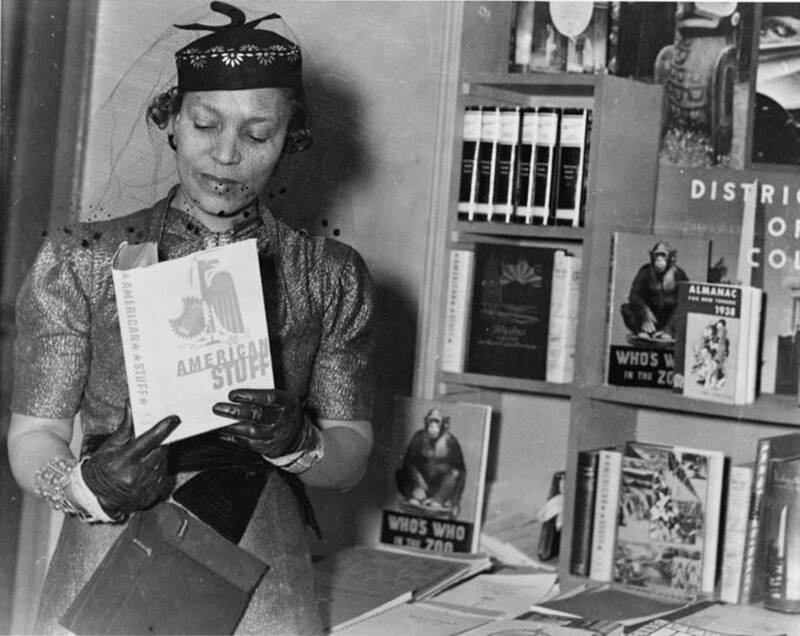

Apart from her acclaimed novel, Their Eyes were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston is most famous for a quote from her essay “How it Feels to be Colored Me”:

Sometimes I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.

She wrote this essay in 1928, the same year she graduated from Barnard, having studied with Franz Boas, the “Father of American Anthropology” (she also studied with Ruth Benedict and was Margaret Mead’s classmate). As we approach the ninetieth anniversary of its publication, Hurston’s essay continues to speak to the complexity of being African-American in the U.S.—and does so with a style and subtlety that mark it as one of the great works of American essay writing.

The popularity of the quote above risks oversimplifying Hurston’s views on race, but it accurately portrays her sense of humor, her love of life, and her determination. She opens her essay with a joke:

I am colored, but I offer nothing in the way of extenuating circumstances except the fact that I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother’s side was not an Indian chief.

A little further on, she informs us:

But I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow damned up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. … I have seen that the world is to the strong, regardless of a little pigmentation more or less.

Taken together with the overwhelmingly positive attitude displayed throughout the essay, it’s easy to see how a casual reader might conclude that Hurston’s experience of being black in America was not so difficult after all.

Such a reading, however, would be at best skin-deep. Her pride, humor, and joy do shine through the words of this essay—and are a large part of what makes reading it so enjoyable—but she has more to say. She lets us know about the fear people in her black hometown experienced, so that even sitting on the front porch as white people rode past was “daring.” She tells us how she first became aware of her racial identity—and how that identity could trump her identity as an individual—when she was sent to school in Jacksonville at the age of thirteen: “… I had suffered a sea change. I was not Zora of Orange County any more, I was now a little colored girl.” She speaks of feeling “surged upon, and overswept” when she was alone in a sea of whites—in her day she was the only black student at Barnard College. She informs us of the cultural distance she sometimes feels from whites, when they are unable to experience black culture with the depth she does: “He has only heard what I felt. He is far away and I see him but dimly across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us.”

Pulled out of context as they are here, the difficulty and pain of these experiences stands out in a way they don’t in the original. Hurston intersperses these vignettes with more upbeat material, tempering their effect. It is tempting to read these stories as the deep, sorrowful heart of the essay, hidden beneath a happier mask. Certainly, Hurston was self-consciously writing for a predominantly white audience, and that may explain her oblique approach to her suffering, but it would be inaccurate to see her descriptions of joy, strength, and triumph as a comic facade concealing a tragic core. She presents her racial identity as differing in different situations and her varying experiences of being black as true to various contexts. We need a better metaphor.

Fortunately, Hurston provides us with one:

But in the main, I feel like a brown bag of miscellany propped against a wall. Against a wall in company with other bags, white, red, and yellow. Pour out the contents, and there is discovered a jumble of small things priceless and worthless. A first-water diamond, an empty spool, bits of broken glass, lengths of string, a key to a door long since crumbled away, a rusty knife-blade, old shoes saved for a road that never was and never will be, a nail bent under the weight of things too heavy for any nail, a dried flower or two still a little fragrant.

Everything in the bag is real, the beautiful as well as the ugly, the joyful as much as the sad. In contrast to the rest of the essay, however, it’s the sadness that stands out here—if we pay attention. In a list of items mostly composed of a few words each, we find three progressively longer ones tucked away: “a key to a door long since crumbled away,” “old shoes saved for a road that never was and never will be,” “a nail bent under the weight of things too heavy for any nail.” What door was she hoping to open with that key? What road was she planning to walk on with those shoes? And what weight bent that nail?

It was the nail that really got me: a perfect metaphor hidden in plain sight. I’m sure Hurston would say we all carry around a few such nails. She suspected that we could dump all our bags in a big pile and refill them at random “without altering the content of any greatly.” In the context of her life and this essay, however, how can we not read this nail as a metaphor for the burden of being black in America? Hurston embraced that burden:

No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory. The world to be won and nothing to be lost. It is thrilling to think—to know that for any act of mine, I shall get twice as much praise or twice as much blame. It is exciting to hold the center of the national stage, with the spectators not knowing whether to laugh or weep.

She couldn’t, however, completely escape it. She couldn’t just be “the unconscious Zora of Eatonville” in the eyes of the country that was her home. The identity she discovered at age thirteen left her “a fast brown—warranted not to rub nor run.”

While that burden of being African-American has lessened in the years since Hurston wrote this essay, we would be deceiving ourselves to pretend it had evaporated away completely. Why did I go through all of high school and two years of college before even hearing the name, Zora Neale Hurston? Why did I learn about her through the anthropology department and not the English department? Why, in 1960, did she die in poverty at a charity hospital and end up buried in an unmarked grave? In 1973 Alice Walker searched for Hurston’s grave. All she could find was an unmarked grave in the vicinity where Hurston was said to be buried. She chose it and marked it with a gravestone hailing Hurston as “A Genius of the South.”

Reading this essay nearly a century after it was written, it is still difficult to know “whether to laugh or weep.” In spite of all the obstacles in her way, Hurston became one of the greatest writers in American literature, and she enriched our collective intellectual and spiritual life. Her contributions, however, went unappreciated during her lifetime and for more than a decade after her death. Were it not for the efforts of Alice Walker, her work would probably still be languishing in obscurity, out-of-print. Hurston’s essay offers us a picture of being black in America that is complex, replete with joy and sorrow, triumph and injustice. Her life and death bore out that picture.

So what are we to think? What are we to do? Hurston gives us a new metaphor for racial identity that affirms both the differences in our experiences and our shared humanity. Like most great writers, she does not give step-by-step instructions; she gives us an opportunity to think about ourselves and others in new ways. She gives us another experience to put in our little bags—an experience we can all share—and the hope that someday all of our bags may be able to hold as much as hers did.

Of one thing, however, we may be certain, the flowers of her life’s work are as fragrant today as they were when she first pressed them between printed pages.

[This essay originally appeared on my blog, “Ten Thousand Li: A Journal of Travel, Exploration, and Art” (http://www.tenthousandli.me).]

Stephen Boyanton received his PhD in East Asian History from Columbia University in 2015. He currently lives in Sichuan province, China, where he works as a writer, teacher, and translator.