I. Entomology

It is in rare circumstances that the etymology of the word is as fascinating as the definition of the word itself. In the case of “vampire,” this is because the precise etymological origins of the word are obscured—both through years of cultural exchange and language migration, as well as the linguistic misrepresentations of these migrating patterns. Thus, “vampire” as a unit of language becomes as mysterious and shifty as the thing it denotes.

The OED points to the year 1745 when the word nestled into English, via the French “vampyre” and the German “vampir.” It’s navigation into English came through the cross-continental fascination with folkloric beliefs, particularly those pertaining to the reanimated corpses wreaking havoc in eastern and central European villages. The word itself is of Slavonic origin: the German “vampir” becomes the Bulgarian “vapir” or “vepir” → Ruthenian “vopur” → “opyr” → “upyr” → pointing to the Russian “upir.” The Austrian/Slovene philologist Franz Miklosich suggested the Turkic origin “uber”, meaning witch. While the conflation of these two powerful beings—the witch and the vampire—does prove compelling, ultimately this theory has been largely abandoned.

More recently, attention has turned to the Greek origins of the word. In a brief 1949 article, the entomologist Malcolm Burr offers the Bosnian word for vampire, “lampyr,” as derived from the Greek “lampyris,” or glow-worm. He notes the Slavonic split between the “l” and the “v” is far from rigid, thus making the sonic and symbolic slippage from the “lampyris” glow-worm to the vampiric “vampire” all the more conceivable.

The “lampyris/vampire” slip presents the challenge to step into the minds of the original Slavonic speakers. Imagine encountering a rare species of flying glow-worms for the first time. In the night, the lights of the adult fireflies, or the glow-worm larvae, would sporadically illuminate the darkness, creating a scene equal parts mesmerizing and haunting, ethereal and devilish. The sight of the glow-worms’ disembodied luminosity would have felt, to some, like stumbling upon a demonic rite. Thus, having no prior experience with the glow-worms, the early Bosnians would associate the Greek word “lampyris” with the spectral terror of the glow-worm. The accumulation of this sinister connotation would, over time, create a new word to signify any dark, otherworldly phenomena. Enter the vampire.

II. Consumption

The vampire itself needs no introduction. Its entrance is scored with booming organ music or shrieking violins. All eyes turn to the shadowy figure descending the staircase, or trespassing the bedchambers of its next victim. Like the glow-worm, the vampire enchants its audience with the allure of beauty and terror.

The literary critic—and prototypical eccentric—Montague Summers provides a conceptual history of the vampire. In The Vampire in Europe, he gestures to a prominent early depiction of the vampire in the Greek myth of Lamia (5). In her anguish, after her children are destroyed, the once beautiful Lamia becomes a serpentine monster and devourer of children.

It is this consumptive pattern of Lamia, the cannibalistic satisfaction of rage and anguish, that has permeated vampire lore. The OED defines both Lamia and the vampire as a blood-sucking entity—the “lamia’s” bloodthirst satisfied specifically through children. Nourishment serves as the categorical barrier between the vampire from other nefarious agents like the demon or ghost. Whereas a revenant or ghost is also nightmarish, the vampire is always hungry. Of course, Summers’ account of vampire lore isn’t entirely predicated on blood drinking, but on the ritual of consumption to appease the dead. Practices like the baking of cakes (called “souls”) on November 1st, to be used as offerings for hungry spirits in parts of Germany and Austria, serve as examples of vampirism manifesting in folk beliefs and rituals (13). To devour the “soul” is an allegory for the dead devouring the living, and the dead and living becoming one.

Consumption, then, is not a destructive force, but one of combination. In drinking the blood of its victim, the vampire joins itself to the victim’s body, the victim’s blood joining the vampire’s body.

III. Sex

Yet, where consumption creates its meaning, it is combination that challenges the taxonomy of the vampire. While it is relatively simple to conceive of the vampire—one has only to imagine the cape, the coffin, or the fangs before the entire mental image of the vampire completes itself—the vampire is almost impossible to conceive. The genealogist of the vampire finds difficulty in delineating its precise classification. As it straddles the ontological boundary of life and death—the undead, the living dead—the vampire challenges the distinction between the two conditions. It sends its victims to the grave, bringing death to life, unless, of course, these victims rise again.

The early Greek philosopher Empedocles provides an account of the world involving only two forces: “Love” and “Strife”. Strife is repellent and destroys; Love is attractive and combines. The natural inclination towards the vampire might be fraught with strife: it is a monster—repellent, feared, and meant to be feared. Yet, in practice, the vampire is the embodiment of love; not only does it combine life and death, but it actively and continuously attracts. The immortality of the vampire—both by definition and in culture—serves as a testament to its appeal. The vampire is alluring; it must be invited in.

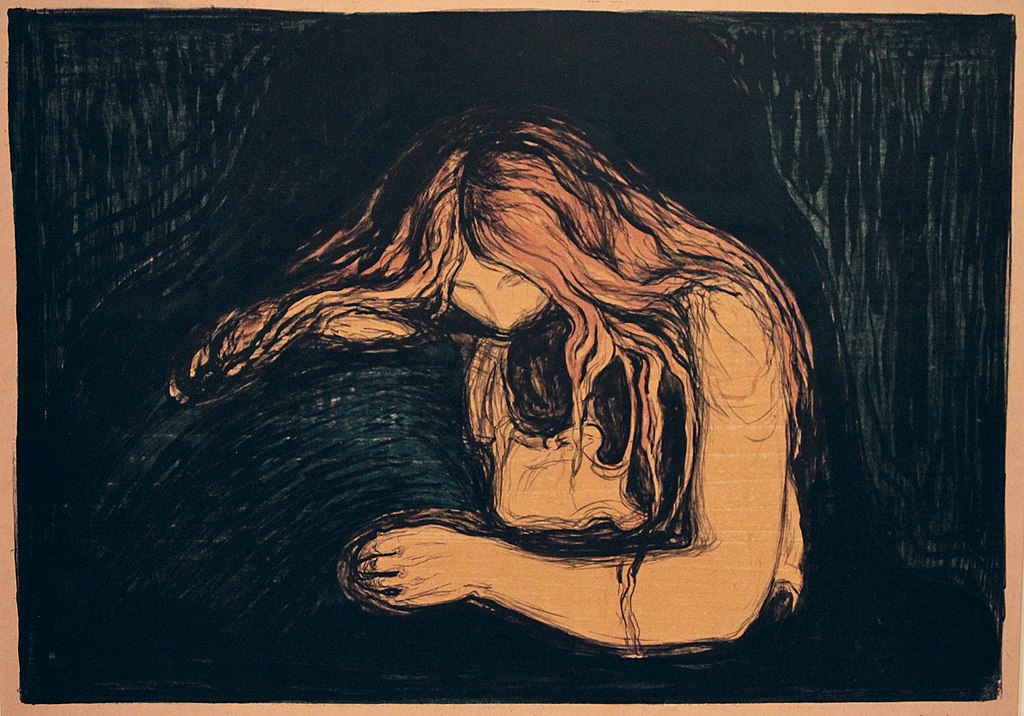

As an embodiment of Love, then, the vampire is intrinsically connected to sex. This is not a new observation: any popular novel featuring the vampire—Victorian or otherwise—is rife with sexual innuendo, if not explicit content. The combination of bodies, and the preying on the blood of one body for another, becomes an obvious metaphor for intercourse. The sexual prowess of the vampire, however, is highly individualized. In Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella, Carmilla, for example, the titular vampire’s beauty is enhanced by “that graceful languor that was peculiar to her.” The vampire’s uniqueness in taxonomic classification—its rareness—creates sexual allure. In Carmilla, this is how the vampire sustains herself; she draws on the desires and attraction of the narrator, Laura, as a means to obtain blood (“peculiar” in the novella also becoming “queer”). Love, manifested in the vampire, creates more Love, and thus perpetuates itself.

IV. Collapse

When Summers introduces Lamia, he introduces her not as the child-eater of the myth, but as the object of love in Keats’ eponymous poem. Lycius, the young Corinthian whom Lamia seduces, becomes entranced, “murmuring of love, and pale with pain.” Yet, the vampire is no object, and Lamia reveals her true nature to Lycius at the end of the poem:

“A Serpent!” echoed he; no sooner said,

Than with a frightful scream she vanished:

And Lycius’ arms were empty of delight,

As were his limbs of life, from that same night.

On the high couch he lay!—his friends came round

Supported him—no pulse, or breath they found,

And, in its marriage robe, the heavy body wound.

While the myth of Lamia becomes warped through time, turning from that of a scaly fiend to a powerful seductress, here the beautiful woman and the snake collapse and become one. Combination is complete, love is captured, and the lover dies.

This collapse of identities is often inevitable for the vampire. In Carmilla, a cat-like beast and a beautiful young woman are revealed to be one and the same. The collapse of the human and monster distinction seen in both Lamia and Carmilla point to that combinatorial effect of Love. Yet the text of Carmilla is deeply interested in a linguistic collapse, as well. Three names thought to signify three individuals are anagrams of one another, and are revealed to signify the same being: “Millarca” ↔ “Mircalla” ↔ “Carmilla.” Likewise, all the letters contained in “Lamia” are in these names, the text of one building on the base of the other.

As the “l”/“v” dichotomy becomes slippery, and the “lampyris” glow-worm becomes the modern vampire, the word itself becomes seemingly divorced from its initial meaning. Even as the human monster distinction is toppled, rarely—if ever—does the vampire shapeshift into the glow-worm. Yet, it is quite possible to imagine a shared conceptual and etymological origin for the vampire, as the “lampyris,” the “lampyr,” and the “Lamia” may have the same ur-language root through the stem “lam”—a parent of all sinister progeny. As Lamia is one of the first iterations of the vampire, her name simultaneously comes from, and becomes the linguistic precedent for the vampire. Her children—killed in the myth from which she was born—become the glow-worms, the folklore beliefs of the re-animated dead, Carmilla—and other 19th century villains—and the word “vampire” itself. Thus, mirroring the collapse of identities in the vampire, the seemingly separated conceptual and etymological origins also become one and the same.

Sam Wilcox is a junior in Columbia College studying English and Philosophy. He has never actually met a real vampire, though he swears they exist, and is getting worried that his propensity for garlic is keeping them away.