Growing out of a Fall 2017 project initially submitted for Professor Richard Sacks’ “The English Sonnet” course at Columbia University, Emily Sun’s essay is an analysis of a critical edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Sonnet—To Science.” The edition was produced by Sun herself from a number of existing editions of the poem, and is contained in the Appendix above.

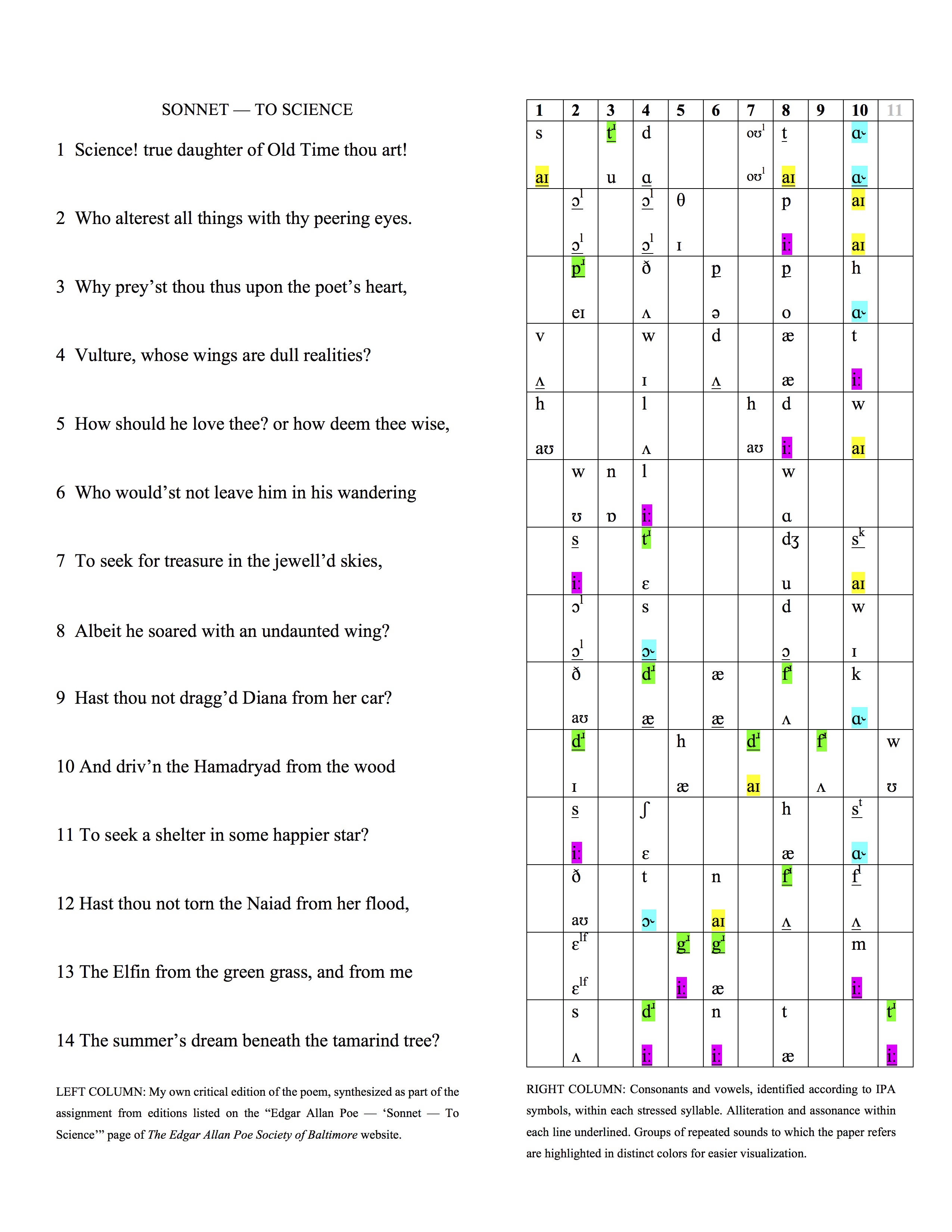

Edgar Allan Poe’s “Sonnet—To Science” ostensibly reprimands the dogmatism of science for altering “all things with [its] peering eyes” (refer to the image above, Appendix 2). The sonnet seems to conceive of science as a hindrance to poetic imagination and creativity, as it preys “upon the poet’s heart” (3) like a “Vulture, whose wings are dull realities” (4), while the poet formerly “soared with an undaunted wing” (8). Poe blames science for disenchanting mythological and poetic stories by divorcing them from the realities to which they were once attached, having “dragg’d Diana from her car” (9) and “driv’n the Hamadryad from the wood” (10). Simultaneously, however, Poe manages to complicate this stance, disputing the total restrictiveness of science on the poetic imagination and implicating poetic creation as a destructive act instead. By employing a number of mythological and literary allusions, Poe ultimately depicts both science and poetry as integral to the inevitable and essential process of creating new narratives and revitalizing old ones, finally positing his own sonnet as an installment in the same creative cycle.

Poe begins to acquit science of the charge of limiting poetic imagination by granting it the epithet of “Vulture” (4), evoking various allusions to classical mythology that signify a broadening rather than narrowing of worldview. The sonnet’s explicit mention of the overtly mythological figures of Diana, the hamadryad, and the naiad (8) invites further associations with classical mythology. One such association is with the death demon Eurynomos, who reclines upon a vulture’s hide in Hades as he consumes the flesh of corpses (Gantz 128). While science restricts the poet’s search “for treasure in the jewell’d skies” (Appendix 7), the otherworldly—or, more accurately, underworldly—placement of science beside Eurynomos conceives of an expanded rather than contracted universe. Eurynomos is also one of Penelope’s suitors in the Odyssey, son of the Ithakan elder Aigyptos and brother of Antiphos, who is one of Odysseus’ crew eaten by Polyphemos during their return from Troy (Homer II.14-22). Eurynomos’ bloodline binds him to the Ithakan homeland. Yet, because his father’s name evokes a foreign region, and because his brother voyages into and perishes in a faraway land, Eurynomos’ existence affirms the existence and accessibility of realms beyond home. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, another mythological Eurynomos is a centaur that participates in the violent battle against the Lapiths during the wedding of Pirithous and Hippodameia (Ovidxii.210-315). The destructive Centauromachy, often interpreted as a representation of the broader conflict between civilization and barbarism, simultaneously recognizes the existence of extra-societal populations and cultures. Even the name “Eurynomos” itself denotes anti-dogmatism, as Greek “eurús” means “wide, broad, spacious,” and “nomós” means “arrangement, law” (Lidell and Scott). So, the “wide law” that is the vulture of science could refer to either a strict dogma encompassing a wide range of phenomena, or instead a law that is broad in the sense that it is lenient and accommodating.

The nature of science as a purely restrictive and dogmatic force is further undermined by the fact that six sentences in the sonnet, including the last sentence, conclude with question marks (Appendix 4, 5, 8, 11, 14). Nearly the entire sonnet can thus be interpreted as a series of questions that are never decisively answered. The speaker asks whether science has torn “from me / The summer’s dream beneath the tamarind tree?” (13-14), but ends the poem without explicit affirmation or denial of the fact. With the possibility of a negative answer, the poem consequently seems less critical of science. Moreover, if science is indeed a vulture, it has not partaken in killing the “poet’s heart” (3), which was already dead before it was carrion to be consumed. Even the death demon Eurynomos consumes corpses that are already dead, much like the meat-flies to which his blue-black color is likened and the vulture whose skin upon which he rests (Gantz 128). The Ithakan Eurynomos, too, does not attempt to usurp Odysseus’ kingship until the occurrence of Odysseus’ absence and likely death. Like a vulture, he is present only to feast on the remains.

If science is not the primary force impeding the poet, then perhaps the poet himself is guilty of his self-destruction. Poe portrays science as an entity that “would’st not leave [the poet] in his wandering / To seek for treasure in the jewell’d skies, / Albeit he soared with an undaunted wing” (Appendix 6-8), alluding to the stories of Cain in Genesis and Icarus in Greek mythology. Cain famously becomes “a fugitive and a wanderer” (Genesis 4.12), much like the sonnet’s wandering poet, after bringing his exile unto himself by enviously murdering his brother Abel. Icarus drowns due to his own folly, after failing to heed his father’s warnings and soaring too close to the sun, thereby melting the wax on his wings (Evans 84). Poe implies that, like the fates of Cain and Icarus, the poet’s downfall is the result of his own faults—perhaps his disobedience or hubris. Indeed, the mythological vultures to which science is compared are often employed as punishments for crimes. In the best-known myths, Prometheus disobeys and deceives Zeus—either by defying Zeus’ orders and giving fire to mankind or by revealing Zeus’ deceptive gift of woman to mankind—and is then punished for his actions by being chained to a rock for eternity while a vulture or eagle continually tears out his liver (Evans 244). After Tityos attempts to abduct Leto at Hera’s command, he suffers a similar punishment in Hades, where he is tied to the ground while surrounding vultures consume his liver forevermore (Gantz 39). The blind Phineus, after he either prophesies Zeus’ intentions too clearly, mistreats his sons, or offends Helios by choosing blindness over death, is also plagued by the part-human, part-vulture harpies, who continually steal and befoul his food (Ovid vii.1-8). If science preys upon the poet like a vulture, and vultures prey upon criminals in the mythological tradition, then Poe seems to intimate some criminality on the poet’s part.

Perhaps the poet’s guilt arises from his attempts to violate the status quo—or even the established cosmic order. The crimes to which the poet alludes—of Prometheus, Tityos, Phineus, Icarus, and Cain—can all be conceptualized as usurping a natural or cosmic order. By either gifting fire or revealing Zeus’ deception to mankind, Prometheus bestows greater power unto mankind while decreasing Zeus’ power as chief god. In other stories, Prometheus undermines Zeus’ authority by withholding from him a secret: that a child by Zeus and Thetis would be mightier than Zeus and ultimately cause his downfall (Evans 244). Similarly, Tityos is punished for his attempt on Hera’s orders to attack Leto, the mother of Zeus’ illegitimate progeny. If successful, Tityos’ transgression would again detract from Zeus’ position at the head of the Olympic pantheon by lending Zeus’ wife Hera greater control over him. Multiple versions of Phineus’ misdeeds in the mythological tradition likewise involve his violation of some sort of preordained law or order: His gift of prophecy grants him—a mortal—power that threatens Zeus’ authority, his willingness to become blind and live without sunlight is a rejection of Helios’ power as a sun deity, and his mistreatment of his sons can be conceived of as a violation of an ethical law. Icarus, too, dies when he attempts to transcend the natural laws that bind mortals to the earth, and Cain’s murder of Abel not only transgresses the system of morality arbitrated by God, but also disrupts the original continuity of his family’s bloodline, as his mother Eve must give birth to Seth to replace the slain Abel (Genesis 4.10-25).

Poe insinuates that the poet’s crime is that he performs a similar act of usurpation by divorcing long-standing mythologies and stories from their associated objects and natural phenomena. It initially seems that science is the one who has “dragg’d Diana from her car” (Appendix 9), “driv’n the Hamadryad from the wood” (10), and “torn the Naiad from her flood, / The Elfin from the green grass” (12-13). However, Poe acknowledges the existence of various mythologies from diverse regions and time periods, mingling the Greek Icarus with the Biblical Cain, the Greek naiad with the Germanic elf, the Roman Diana with the Greek hamadryad. Providing such a succession of myths highlights the fact that the Greek Artemis was dragged from her car by the imagination of a Roman poet who replaced her with Diana, adapting her myth for his own cultural traditions. The naiad, too, was divorced from the flood not by science, but by the creation of later stories and myths, like that of the flood narrative in Cain’s Genesis. Poe’s allusion to the hamadryad driven “from the wood” (10) further underscores the sentiment that poets and storytellers are those who divorce long-existing deities and stories from the natural world, only to imbue the emptied objects with newer deities and stories. Hamadryads, which are “in the opinion of some authors … the longest lived of all mortal beings,” are closely dependent on the trees in which they are born, and killed only when those trees are destroyed (Bell 366-7). Because writing poetry, like writing in general, requires the use of paper, which in turn requires that a tree be felled and destroyed, it is inherently a literally and metaphorically murderous act.

The violence of transforming a tree into a piece of paper is foreshadowed in Poe’s earlier use of “leave” (Appendix 6), which not only means “to allow,” but also denotes the foliage—or growth in general—of a tree or the pages of a book (OED). A poet displaces the metaphors residing in a tree or any other object in favor of a new metaphor, and thus “alterest all things” (Appendix 2) by creating the new narrative. Poe even performs such a displacement and substitution upon multiple segments of the sonnet by altering them across various editions, most notably changing s lines 11, 13, and 14 for the Graham’s Magazine edition, in which the insertion of “the dainty fay” replaces “and from me” in line 13 (“Edgar”). Poe has moved the poem from its initial state as an independent entity, first to function as the prelude to the poem “Al Aaraaf,” and then again to insert it into an entirely different story, “The Island of the Fay,” for the Graham’s edition. In order to better suit his new story, he modifies the sonnet, removing and replacing whole lines at will (“Edgar”). The “flood” in line 12, like the flood of Greek myth survived by Pyrrha and Deucalion (Evans 90-1), or the Biblical flood survived by Noah’s family (Genesis 7), hints that poetic creation is a violent, destructive process. Only after such destruction can the flood survivor or poet repopulate the earth or page with new people and new stories.

The poet’s act of destructive replacement is furthermore reflected in the gradual shift, one letter at a time, between the three consecutive, stressed syllables of “art” (Appendix 1), the first syllable “alt” in “altered” (2), and “all” (2). The poet’s repeated displacement of one letter for a new one continually changes the meaning and identity of each successive word. Similarly, the poet elides the “e” in the second-person and preterite verbs “prey’st” (3), “would’st” (6), “jewell’d” (7), “dragg’d” (9), and “driv’n” (10), signifying its omission by replacing it with an apostrophe. The inherent destructiveness of creating poetry is also evoked by Poe’s pronouncement that the poet “soared” (8), homophonous with “sored.” The poet embarks on his flight of fancy with the guarantee that he will also become “sore,” himself the object of harm, and even perhaps “sore” another, as the subject enacting harm (OED). The inclusion of the preterite verb “soared,” as opposed to the present-tense verb “soar,” implies that the simultaneous acts of imaginative creation and destruction are immutable, inevitable facts, fixed firmly in the past.

The inevitability of Icarus’ fall—and the fall of the poet—is even foreshadowed via the enjambment in line 6. Although the poet, as well as Icarus, is left “in his wandering / To seek for treasure in the jewell’d skies” (6-7), unbounded by the end of the line just as he is unbounded by the limits of the earth, the comma at the end of line 7 ultimately demarcates the bounds of his movement. Poe’s use of the restrictive sonnet form itself, with its various associated conventions, highlights the poet’s struggle to exercise the full extent of his imagination within a relatively rigid structure. With the exceptions of the 1829 edition; the 1831 edition, in which the poem was published as a prelude to “Al Aaraaf”; and the 1841 Graham’s Magazine edition, in which the poem was included in “Island of the Fay”; the poem’s title includes the word “Sonnet” (“Text”) restricting the poem to the expectations traditionally attached to the sonnet form before the first word is even read. And with the first word, “Science!” (Appendix 1), which unexpectedly places the first stress of the sonnet on the first syllable, the sentence ends prematurely with a caesura. The first word of “Science!” also introduces to the sonnet a concept that seems to be the antithesis of love, the traditional object of a sonnet. The poet’s own creative vision thus struggles against the limits of the sonnet form and tradition.

By both partially acquitting science of its stifling dogmatism and partially indicting poetic creation as a destructive act, Poe implies that both disciplines yield similar consequences. Both, in seeking to describe the natural world, seem to restrict, destroy, and usurp the power of other stories that previously described the natural world. The rational, evidence-based practice of scientific inquiry banishes magic and mythology from the aspects of the world it examines. Similarly, poets, in order to tell new stories about the world, must banish and replace older metaphors and myths associated with it. The sonnet’s first line implies that both disciplines similarly perform these functions of usurpation. The poet’s exclamation of “Science! True daughter of Old Time thou art!” (1) suggests science’s similarity to poetry and mythology: “Art” denotes the second-person singular form of “to be”; “a practical pursuit or trade of a skilled nature,” much like science; or “any of various pursuits or occupations in which creative or imaginative skill is applied according to aesthetic principles” (OED), much like writing poetry or generating stories. Furthermore, science is placed within the Olympic pantheon via the epithet “true daughter of Old Time.” If “Old Time” is taken to refer to the Titan Kronos, then his daughter, Science, could be Hera, who does usurp Kronos’ place of authority with her siblings (Evans 81). Because Kronos derived his power from overthrowing his father Ouranos (288), perhaps his true daughter is not necessarily one who is “true” in the sense that she is “loyal,” to him, but, in the “real” and “steadfast” senses of “true” (OED), one who unswervingly follows his example and deposes him, just as he did to his father. The cycle continues, of course, as the subsequent allusion to the vultures that tear at Tityos acknowledges the fact that Hera is concerned about the possibility that her power might be usurped. Although Hera becomes queen of the gods after Kronos is overthrown, she is threatened by Zeus’ act of siring divine children—Artemis and Apollo—by another mother, Leto. Her singularity and position of power, however, are already undermined by the non-exclusive epithet of “daughter of Old Time,” which could refer to her sisters Demeter or Hestia as well (Evans 81). The lack of capitalization of “true,” despite its position at the beginning of a sentence, un-deifies the apotheosized Science/Hera, challenging her authority by denying her the status of a proper noun. The association of vultures with Eurynomos further evokes the usurpation of the mythological Eurynome, who, according to one account of Greek creation, served as the original creator of all things before being overthrown by Saturn/Kronos (Evans 110-11). Science is caught amid a cycle as both the usurper and the authority on the verge of being usurped—much like Eurynome, Kronos, Zeus, Hera, and the mythical stories of the past upon which science preys.

That narratives of usurpation exist at the cosmic level, and form the very backbones of classical myths of creation and divine succession, implies that these narratives are inevitable. Such acts of displacement are cosmically predetermined, stemming from the original, ur-usurpation narrative of Kronos overthrowing father. Science’s act of “peering” (Appendix 2)—included in all editions except for that of the 1830 Saturday Evening Post and its reprint in The Casket (“Edgar”)—implies not only that scientific study involves observing and examining natural phenomena, but also that the poetic narratives it usurps in favor of its own observations and theories are “peers” of—in the sense that they are “equal to” (OED)—scientific narratives. The use of the variant “meet” instead of “true” in line 1 (“Text”) functions in a similar manner, lending a sort of legitimacy to the usurping narrative that is at least of equal degree to the legitimacy of its predecessor.

The legitimacy and cosmic inevitability of such usurpations are reinforced by Poe’s allusions to Cain and Prometheus. Despite Cain’s criminal actions, God determines that “Whoever kills Cain will suffer a seven-fold vengeance” (Genesis 4.15). By protecting the murderous Cain, God seems to designate Cain’s disruption of the moral order, as well as of the order of his family’s bloodline, as somewhat permissible. Prometheus, as the gifter of fire to mankind, is responsible for the creation and development of all civilization. Thus, his criminal action that threatens the cosmic hierarchy is viewed not only as permissible, but vital for human life. This cycle of alteration is portrayed as an almost holy process. The stem of the word “alterest” (Appendix 2) is, after all, homophonous with “altar,” a site of religious worship. The homophony between “prey,” the stem of the violent verb “prey’st” (3), and “pray,” which again denotes an act of worship, further conflates violent destruction with pious, religious practice. So, the repeated alteration, destruction, and replacement of narratives and metaphors, whether via the replacement through the ages of one mythological story with a newer story, or via the replacement of a mythological story with a newer scientific theory, is a process that is both necessary and inevitable for civilization to healthily progress.

Indeed, the nature of science as a vital, creative force is signaled in the very first line of the sonnet. Here, Poe’s apostrophe to science is reminiscent of the invocation of a Muse as a source of poetic inspiration. Science further takes the place of the poet’s beloved that is the impetus for writing a traditional love sonnet, as Poe—the poet himself—addresses science, “How should he love thee?” (5). This productive ability of science is ascribed to poetry by Percy Shelley, whose work Poe admired and praised (“Percy”), in A Defence of Poetry:

But poets … are not only the authors of language and of music, of the dance, and architecture, and statuary, and painting: they are the institutors of laws, and the founders of civil society, and the inventors of the arts of life, and the teachers… Poets, according to the circumstances of the age and nation in which they appeared, were called, in the earlier epochs of the world, legislators, or prophets: a poet essentially comprises and unites both these characters. For he not only beholds intensely the present as it is, and discovers those laws according to which present things ought to be ordered, but he beholds the future in the present, and his thoughts are the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time. (Shelley)

According to Shelley’s definition of a poet, scientists, who invent new descriptions and discover new laws of the natural world, perform the same necessary, generative function as do poets.

The inevitability of the cyclic usurpations of and by scientific, mythological, and poetic narratives is furthermore evident upon closer inspection of lines 9-12. The mortality of the mythological Diana is inherent in her very name: The first syllable of her name is homophonous with “die.” Diana’s existence and legitimacy—at least that of her Greek counterpart—is threatened by Tityos, whom she and her brother slay in some versions of the myth after he attempts to attack their mother. The ultimate destruction of Diana’s myth is then reflected in the disassembly of the components of line 9 (“Hast thou not dragg’d Diana from her car?”), which are cannibalized and rearranged in line 10 (“And driv’n the Hamadryad from the wood”). Notably, the /dɹ/, /d/, and /æ/ sounds are reused in line 10, and the prepositional phrase beginning with “from” is adopted once in line 10, once in line 12, and twice in line 13. A similar phenomenon manifests in the repetition of the words “How” (5) and “Who” (2, 4, 6), which are rearrangements of the same three letters into different words with different meanings. Again, the sort of usurpation performed by science and art can be productive and generative.

This notion is present in the myths of Prometheus and Tityos, too, whose bodies are doubly creative. The livers of the two figures are at once eaten by the vultures, metabolized into a new source of energy and sustenance for another organism, and repeatedly regenerate themselves. Just as destruction makes room for the growth of newer liver cells, so does the destruction of a story make room for the growth of newer ones. Diana and the hamadryad, though displaced, are allowed in all but the Graham’s edition of the poem (“Edgar”) “To seek a shelter in some happier star” (Appendix 11). Forced out from their current abodes, they actually expand the breadth and reach of their stories by venturing farther, into the heavens. The generation of such a story occurs in the myth of Orion, to which the “happier star” of lines 9-11 potentially alludes: After Orion’s death upon Earth at the hands of Diana/Artemis, his legacy is not destroyed, but displaced to and recreated in the heavens in the narrative form of a constellation (Evans 219). The “dead” story is reanimated, albeit in a different guise.

Poe acknowledges that even the new narrative he is currently generating—that of “Sonnet—To Science”—is not immune to this process. After shifting from the naiads of classical mythology and the flood of Genesis in line 12 to the elves of Germanic mythology at the beginning of line 13, Poe shifts the focus to himself in the first and only instance of a first-person pronoun in the sonnet. He laments that soon “from me / The summer’s dream beneath the tamarind tree” (13-14) will be torn. By concluding the sonnet with a reference to himself and his own imagination, Poe presents the poem he himself has written as the latest in the long succession of narratives to which he alludes. This notion is echoed in line 8, where Poe subtly inserts himself in the word “Albeit,” which sounds similar to “I’ll be it” and “all be it”—it is as if Poe considers himself, along with all other poets, as among those whose imaginations have “soared with an undaunted wing” (8). For now, it seems that the poem has not yet reached its limits to become entirely antiquated. The inclusion of the “tamarind tree” (14) at the end of the poem inserts an eleventh, unstressed syllable in a line that would otherwise exhibit perfect iambic pentameter. Like the tamarind tree, a relatively new, exotic import to the Americas from Asia during Poe’s time (Mabbott 91-2), the poem’s narrative is still fresh and novel. Poe’s sonnet has only recently been created and begun to displace older stories and metaphors, and is still transgressing and transcending the bounds of the sonnet tradition.

Yet Poe conveys that this freshness will not last for long. Even the novelty of the tamarind will wear off, divorced from the tree like the hamadryad has been divorced from hers, its wood recycled to make new paper and new stories. The beginnings of the poet’s transformation from an active subject performing the act of usurpation, to a passive object that is usurped, are manifested in the shifting distribution of /aɪ/ and /iː/ vowels during the poem’s progression. The former, which rhymes with the nominative first-person pronoun “I,” is particularly dense in the first half of the poem, especially in the eyes/wise/skies end rhymes in lines 2, 5, and 7. However, most notably beginning in line 4 due to the jarring slant rhyme of “realities,” the /iː/ vowel, which rhymes with the accusative first-person pronoun “me,” begins to increase in density. The assonance of /iː/ becomes extremely prominent in the me/tree end rhyme of the final couplet. The poet’s position of agency and power, as the grammatical subject “I,” is decreased as the poem progresses and becomes less new, until he is relegated to the object “me.”

Having suggested that the shared consequences between science and nature include the destruction, alteration, and displacement of metaphors and stories associated with natural phenomena, Poe then implies that science and poetry are in essence the same. Perhaps their commonality stems from the fact that both disciplines involve the mediation and intervention of humans in describing and explaining observed or imagined phenomena. Man is unable to wholly and accurately describe the narratives he experiences or images. Consequently, the constant generation of new narratives and metaphors, as well as the constant alteration and destruction of older ones, becomes a method of arriving at a closer approximation to a full view of the world and of experience. The inevitable, insurmountable remove between man and the phenomena he attempts to narrativize is paralleled by the enjambment that separates “me” in line 13 from “The summer’s dream” in line 14. The use of summer in the possessive case furthermore divorces “me”—the poet—from the dream he hopes to transcribe in the form of a poem, as the dream belongs less to the poet and more to the natural phenomenon of summer.

The disruptive influence of the human on the ability to express reality in its purest, least restricted form is also conveyed through the allusion of the poet’s rude separation from his dream to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s composition of “Kubla Khan.” Coleridge, one of Poe’s notable literary influences (Schlutz 195), writes of a person from Porlock who interrupts him while he is recording his dream that would eventually become “Kubla Khan,” ultimately causing Coleridge to forget the rest of the dream and leave the poem unfinished:

On awakening he [Coleridge] appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole, and taking his pen, ink, and paper, instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines that are here preserved. At this moment he was unfortunately called out by a person on business from Porlock, and detained by him above an hour, and on his return to his room, found, to his no small surprise and mortification, that though he still retained some vague and dim recollection of the general purport of the vision, yet, with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast, but, alas! without the after restoration of the latter! (Coleridge)

Shelley conceives of poetic inspiration and composition as similarly hindered by the poet’s human capacities in his Defence:

Like the fading coal, and Coleridge’s failure, man’s inability to perfectly capture the narratives he observes, experiences, and conceives is resultant of his own inherent insufficiencies. Poe demonstrates such a fault via the repetition of various r-colored vowels in the sonnet, notably within the final stressed syllables of lines 1, 3, 9, and 10. Graphically, these r-colored vowels are identical to the non-r-colored vowel pronounced /ɑ/. However, once the reader vocalizes these vowels, the physical limitations of the reader’s body—specifically of the human tongue and mouth—force the reader to alter the pronunciation of /ɑ/ to /ɑ˞/ in the presence of the consonant /ɹ/. The original sound of the vowel is corrupted only upon human intervention. The forced alteration caused by r-coloring is juxtaposed with various consonant clusters throughout the poem, most notably in the alliterations of lines 9, 10, and 13, which include /ɹ/ as the second consonant but leave the pronunciation of the preceding consonant unaltered. Man can only reproduce a shade or dream of what he observes or imagines, creating an unstable and perverted hybrid that is part-human, like the centaur Eurynomos and Phineus’ harpies.

… the mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness… when composition begins, inspiration is already on the decline, and the most glorious poetry that has ever been communicated to the world is probably a feeble shadow of the original conceptions of the poet. (Shelley)

The corrupting influence and imposition of mankind’s limitations on storytelling thus affect the Icarus-like poet, whose imaginative “wandering” (6) allows him to transcend regular boundaries, but whose nearly homophonous “wondering”—a contemplative act that involves human interpretation and thus the intervention and alteration of an experience by the human mind—brings him back down to earth. Although the poet’s desire to reach the sun and attain purity of expression allows him to transcend to and create at new heights, his true aim is unattainable because he simply lacks the necessary apparatus. Gaining a full view and understanding of the experience cannot be humanly achieved in a single attempt. Instead, it requires, like “Sonnet —To Science” itself, a process of continuous revision.

Emily Sun is a senior in Columbia College majoring in English. She’s mournful at the prospect of her imminent departure from her dear friends and colleagues at the Review, but is excited to be staying on the East Coast to read some more Old English poetry for the next few years.

Works Cited

Bell, John. Bell’s New Pantheon.London: J. Bell, Bookseller, 1790. Print.

Coleridge, Samuel T. The Complete Poems, ed. William Keach. Penguin Books, 2004. Print.

“Edgar Allan Poe — ‘Sonnet — To Science’.” The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. https://www.eapoe.org/works/info/pp026.htm#workskcp

Evans, Bergen. Dictionary of Mythology. New York: Dell Publishing, 1970. Print.

Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. Print.

“Genesis.” The New Oxford Annotated Bible With the Apocrypha: New Revised Standard

Version, ed. Michael D. Coogan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Print.

Henry George L. & Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon. Revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. http://perseus.uchicago.edu/Reference/LSJ.html

Homer. The Odyssey of Homer, trans. Richmond Lattimore. New York: HarperCollins, 1967. Print.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Perseus Digital Library, ed. Brookes More. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0028

“Percy Bysshe Shelley.” The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Web. 30 Dec. 2018. https://www.eapoe.org/people/shellepb.htm

Schlutz, Alexander. “Purloined Voices: Edgar Allan Poe Reading Samuel Taylor Coleridge.” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 47, no. 2, 2008, pp. 195–224. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25602142.

Shelley, Percy B. “A Defence of Poetry.” Poetry Foundation. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69388/a-defence-of-poetry

“Text: Thomas Ollive Mabbott (and E. A. Poe), ‘Sonnet — to Science,’ The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Vol. I: Poems (1969), pp. 90-92.” The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. https://www.eapoe.org/works/mabbott/tom1p029.htm

“The Oxford English Dictionary.” Oxford University Press. Web. 27 Dec. 2017. http://www.oed.com/