The Fool and Other Moral Tales / Anne Serre, trans. by Mark Hutchinson / New Directions, 09/19 – $15 (Paperback)

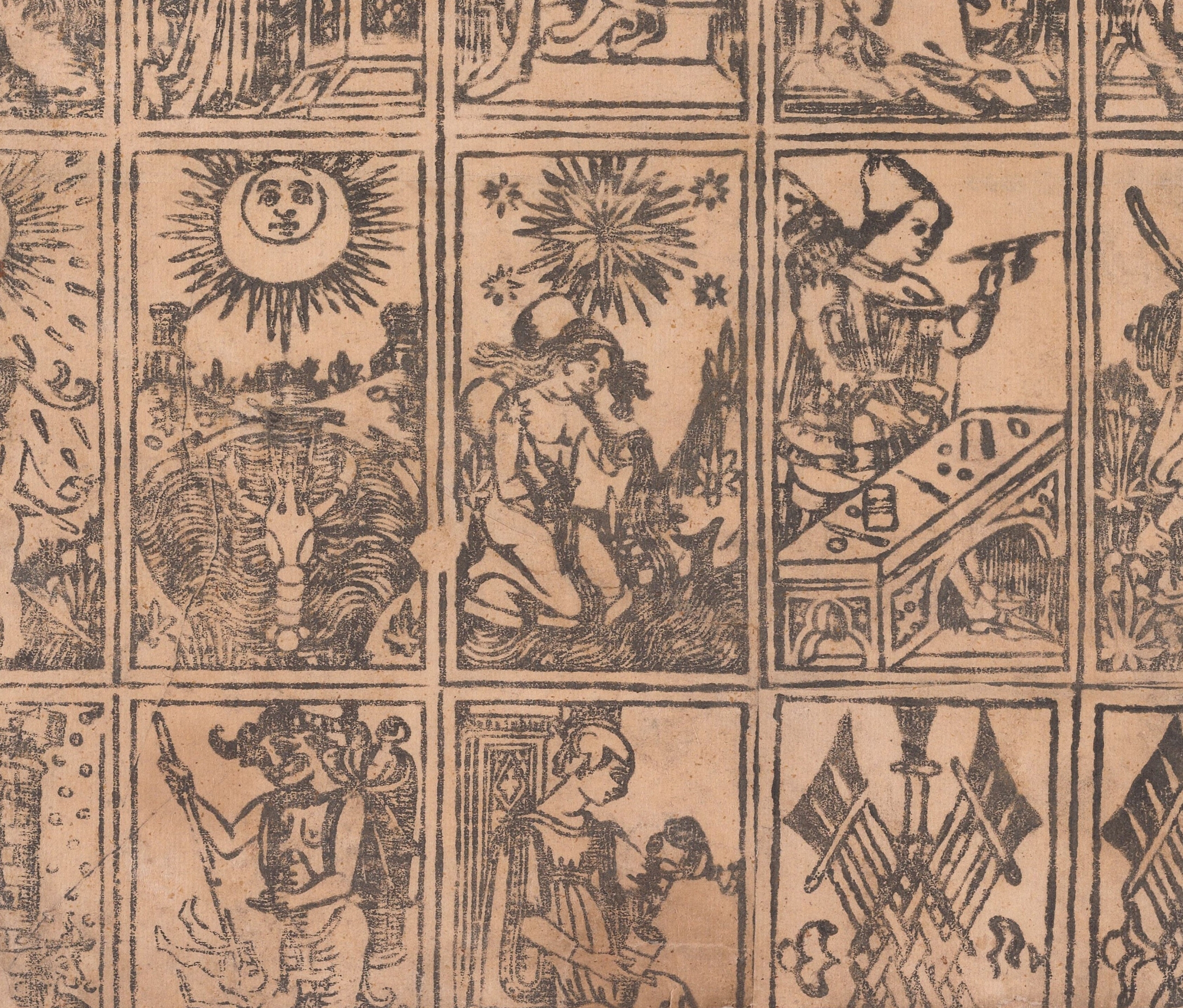

Repulsive, violent, confounding: that’s how I would best describe Anne Serre’s newly translated collection of short stories, The Fool. Yet Serre performs a wild alchemy within the tight confines of the three fabulous tales collected here—she makes the confounding, violent, and repulsive beautiful. It is a collection as mystifying and arcane as the title story’s conceit—a Tarot card come to life—and, like the cards themselves, is ceaselessly captivating, presenting brilliant, perplexing images to be endlessly interpreted.

The collection opens with ekphrasis: the narrator describes her relationship with the intricately detailed Tarot deck, and The Fool in particular. A card which suggests the promise of new beginnings and the humility of the observer is read, by the narrator, as “crude, the colors ugly.” She later draws attention to the impracticality of The Fool’s rucksack, the mysteriousness of the animal at his feet (is it “a dog, a cat, a fox, a hyena or a chimera”?), and the repetition of color between objects, keeping the card in a blur of visual inaccessibility. “The instructions explain that everything in the arcana is important, everything has to be taken into consideration: each little color, each little form or sign,” Serre writes. When the colors, forms, and signs are mutable, however, the meaning of the card becomes opaque.

The stories collected in The Fool, then, become a manual about reading, and reading’s impediments. Where Serre’s narrator, in “The Fool,” is troubled by the titular card’s meaning, the subsequent story, “The Narrator,” directs attention to the speaker themself. The story becomes a narrative about narration, wherein the character, “the narrator,” is seemingly in conflict with the narrative voice of the story. Where two narrators compete for domination, where the methods of reading are put under scrutiny, Serre offers a fiction that is at war with itself.

The landscapes of these stories are brutal. Picking up on the image of the card, Serre imagines cliffs, mountainous terrain, impasses that force the narrator(s) to reckon with themselves and their experiences. It is a collection, however, that considers the domestic, interior spaces of a home, a chalet, as equally dramatic. The final—and undoubtedly the most divisive—story, “The Wishing Table,” takes place in the private house of a young narrator’s family, where the reader is immediately thrust into a space of taboo and incest. The environments of The Fool are not hostile for the sake of the horrific, however. Serre does not seek to revel in grotesquerie. Rather, these environments become places where Serre tests the limits of a fictive imagination. The discomforting sexuality of the final story, the concerns over narrative control in the second, and the haunting presence of The Fool in the first become moves to transcend the boundaries of storytelling itself.

The narrator of “The Fool” must overcome the continual presence of the Major Arcana. The Fool manifests, physically, within the narrator’s life. It is in confronting, finally, the flesh-and-blood image of The Fool that she is able to move forward. The world of reading, of fiction, spills over into the world of the character’s physical existence. Indeed, what I find most remarkable about the premier story in this collection is that it reads less like the strict narrative of an individual grappling with a symbol ever-present in their life, and more like a personal essay—rendering this world at a mid-point between the reality of the everyday, and the world of storytelling . “The Fool,” is flooded with rich literary references, from Eudora Welty to Thomas Mann, bringing the image of The Fool into a voluminous cultural tapestry that exceeds, and includes, Serre’s own voice:

“The Fool roams through the region of which Eudora Welty writes: “It took the mountaintop, it seems to me now, to give me the sensation of independence. It was as if I’d discovered something I’d never tasted in my short life.” And The Fool really is on the mountaintop, for though there are tufts of grass at his feet, on the horizon there’s nothing.”

As she incorporates the narratives and voices of other writers, Serre creates a trompe l’oeil illusion: she hides her fiction in the language of literary discourse, allowing The Fool to bleed off the page.

It is as she slips between genres, as she builds on a multiplicity of voices, that Serre challenges her reader to be critical—to be wary. The voice she adopts is quite deliberate. And as the tales she crafts unwind, these voices often come to conclusions paradoxical, belying the text which comes before, or after. Much like the murkiness of reading Tarot, Serre’s stories are written incongruously: they, too, demand precise, dedicated attention. As her narrator knows to take everything into consideration, “each little color, each little form or sign,” so too must her reader.

To write fiction is to traffic in deceit. Serre’s tales are explorations in that deceit. Where the final narrator is at ease in family’s disturbing sexual interests (which, for readers first approaching Serre’s work, demand a content warning), the project of the final story is to get the reader to—if only temporarily—believe the falsity of this story. It is not a surrender of morality, but sublimation to a tricky narrative voice. These are “moral tales,” in their irony; these are tales that, first and foremost, scrutinize tale-telling. It is in the relationship between the reader, the conniving (or not conniving) narrators, and the author herself, that the deceit is made manifest.

The stories in The Fool are, in a sense, a card game. It is a game where the stakes are, for the reader, to be, or not be, The Fool themself.

Sam Wilcox is a senior at Columbia University studying English. His favorite Tarot card from the Rider-Waite deck is The Hierophant. The keys, the crosses, and the crown make for an image rich with symbolism, one which he will not attempt to read here.