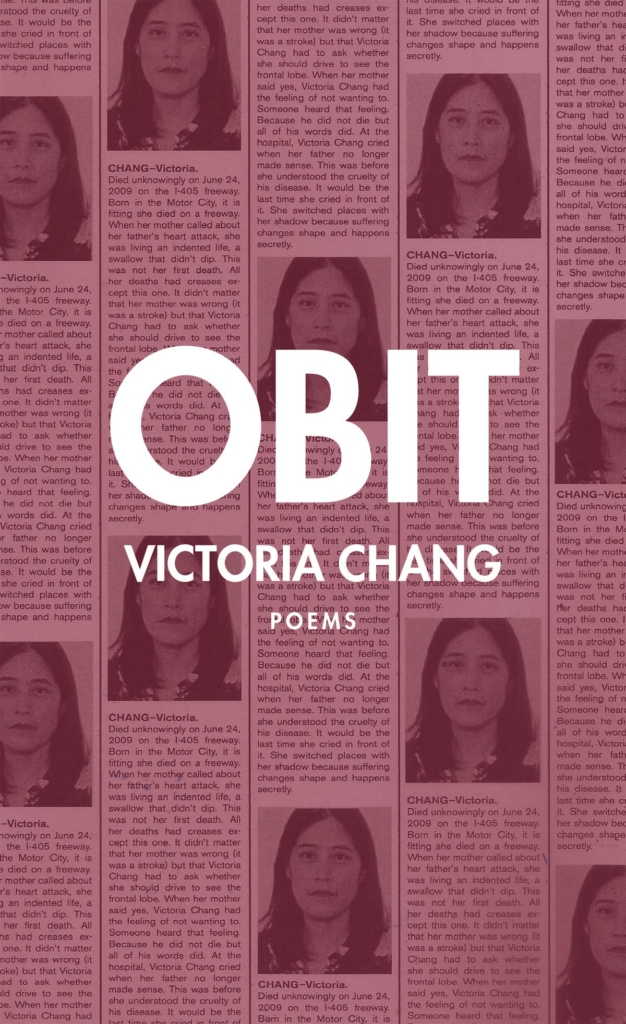

Obit by Victoria Chang

Grief scatters us. In Obit, Victoria Chang attempts to put us back together.

Chang writes to document her mother’s 2015 death and her father’s 2009 frontal lobe damage, but her poems truly rest in the innumerable micro-deaths in between. The death of the mother is simultaneously the death of the mother’s teeth; of appetite; of language; of hindsight; of Victoria Chang.

The book largely consists of 70-odd obits: vertical, dense, tombstone-like poems, each dedicated to a specific loss. Through this rigid form, she entertains, and ultimately rejects, the objectivity and finality of newspaper obituaries. Instead, Chang works to compress grief into various containers, seeing what new shapes it takes under spatial and syllabic confines. She weaves the tanka, a five-line Japanese form, throughout; the second section of the book is a sprawling sequence of elegiac sonnets pieced together by blank space.

Despite their different presentations, the pieces revolve around the same subject. Endlessly self-referential, one death always collides into another. But, with supreme self-awareness, Chang addresses this repetitiveness in its own obit: “Subject Matter—always dies, what we are left with is architecture, form, sound, all in a room, darkened, a few chairs unarranged.” As she writes about death, then, Chang further enacts it. This subject gives way to the form that surrounds and encloses it. Left to stand in the dark and examine our griefs, we have nothing but the imprecise tool of language, its “architecture, form, sound.”

Obit, longlisted for this year’s National Book Award, places Chang’s personal griefs against a backdrop of loss. At the end of the book, she writes, “Since [my mother’s] death, America has died a series of small deaths, each one less precise than the next.” Obit is not quite an invitation into a communal grieving, but more so an acknowledgement of the vagueness present in the immensity of death — an inexpressibility that keeps us returning to language.

-Claire Shang

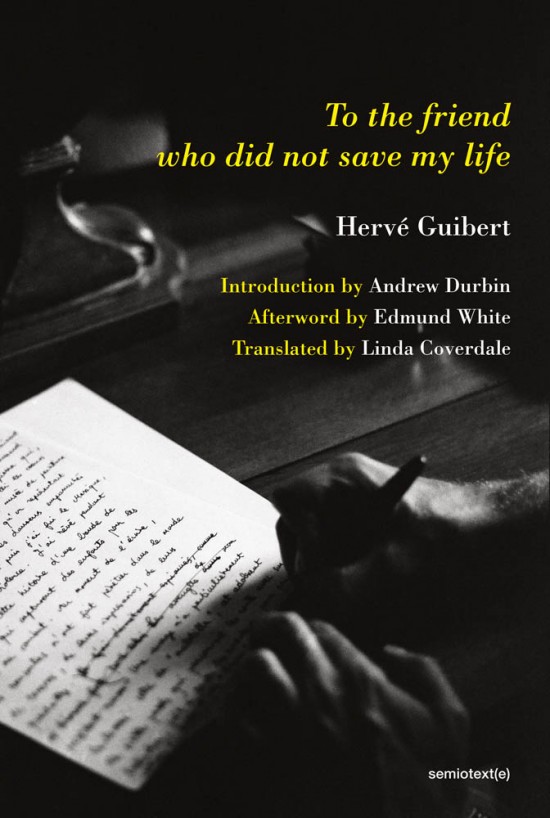

To the Friend Who Did Not Save my Life by Hervé Guibert

Originally published in 1990, Hervé Guibert’s novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life has received a timely reissue this year via Semiotext(e). The novel, which scandalized the French press upon its initial publication for its loosely fictionalized account of philosopher Michel Foucault’s fatal battle with AIDS, made Guibert into an overnight celebrity. A work of autofiction, the novel is an intimate, uncompromising depiction of a life thrown into upheaval by terminal illness. Its fragmented, diaristic form jumps back and forth in time, interweaving the progression of the narrator’s AIDS with the illnesses of his friends and lovers.

Reading Guibert’s novel in 2020, it’s almost impossible to ignore the parallels between the AIDS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the diseases differ both in their pathology and public perception, the context of our current pandemic lends an added urgency and poignancy to Guibert’s writing. There is a shared uncertainty between the early stages of the AIDS epidemic and our similar lingering confusion about many aspects of the coronavirus: how it is transmitted, who is affected by it, and how it can be cured. Perhaps the most poignant parallel to our current moment is the protagonist’s desperate, chimerical hope for a cure—a promise which is dangled by Bill, an opportunistic American businessman and the novel’s titular “friend.” This promise of a cure, which preoccupies the novel’s second half, ultimately turns out to be a false one.

More than merely a controversial flash in the Parisian press, this book stands in company with Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, Virginia Woolf’s “On Being Ill”, and Susan Sontag’s AIDS and its Metaphors, as one of the great works of “illness literature”. This novel helped establish Guibert as the rare writer who is unafraid to look at illness squarely in its face, confronting it in all its loneliness, melancholy, and sorrow, and even its rare moments of beauty.

-Thomas Mar Wee

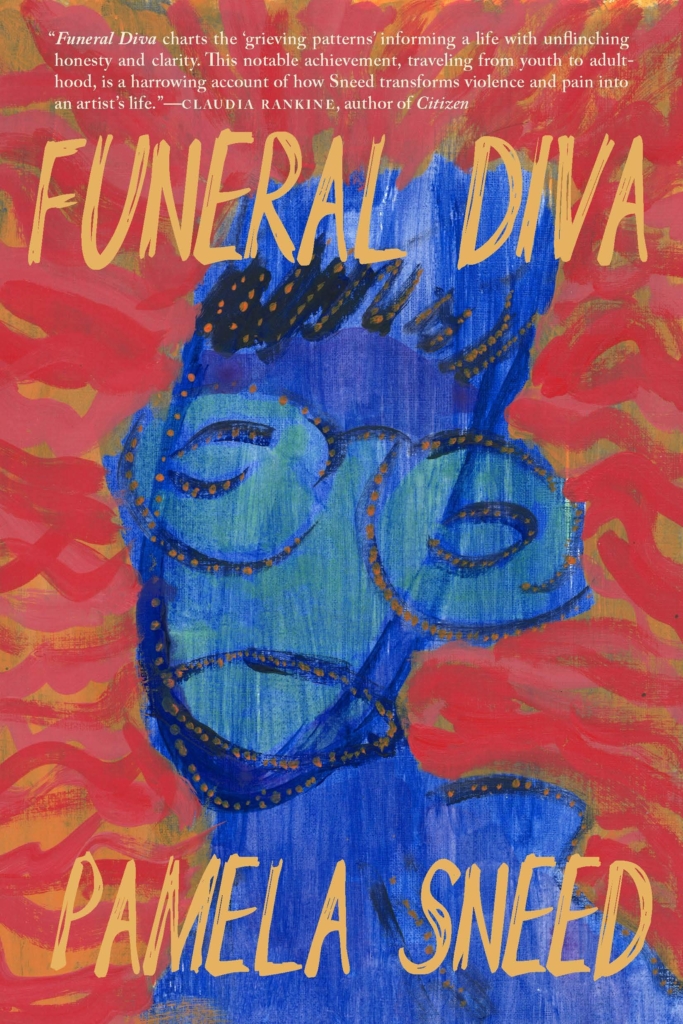

Funeral Diva by Pamela Sneed

Pamela Sneed’s Funeral Diva acts as an emotional roadmap that offers guidance and insight into the familiar chaos of the future. Defying genre, Funeral Diva intricately weaves together memoir and poetry, documenting her mid-20’s in New York City during the AIDS era and her many loves and losses. Throughout her book, I found myself mourning for those I hadn’t met but felt like I knew through her prose. The best way I can describe reading her work is that it’s synonymous to the painful prickle of a broken heart and the familiar scent of home after a long trip away. A balm for chapped lips. A warm bath.

Acting as a Bildungsroman, but with more grit than traditional versions, Sneed’s blunt yet deft chronicle links together past and present as she narrates her coming-of-age as a Black queer woman. Her occasional jaunt into deeper memories of adolescence, desire, and trials create a tapestry, textured by a visceral collection of poetry, cultural references, and wit. What’s most notable about Sneed’s work is her steadfast honesty as she traces the threads of lovers past and present and her reflections on the AIDS epidemic as she draws parallels to our current debacle with COVID-19. Sneed’s rapturous love for her friends feels almost cathartic in these times. Her line which haunts me the most and fills my mind with further questioning: “Who will care for our caretakers?” The implications are vast.

-Bella Barnes