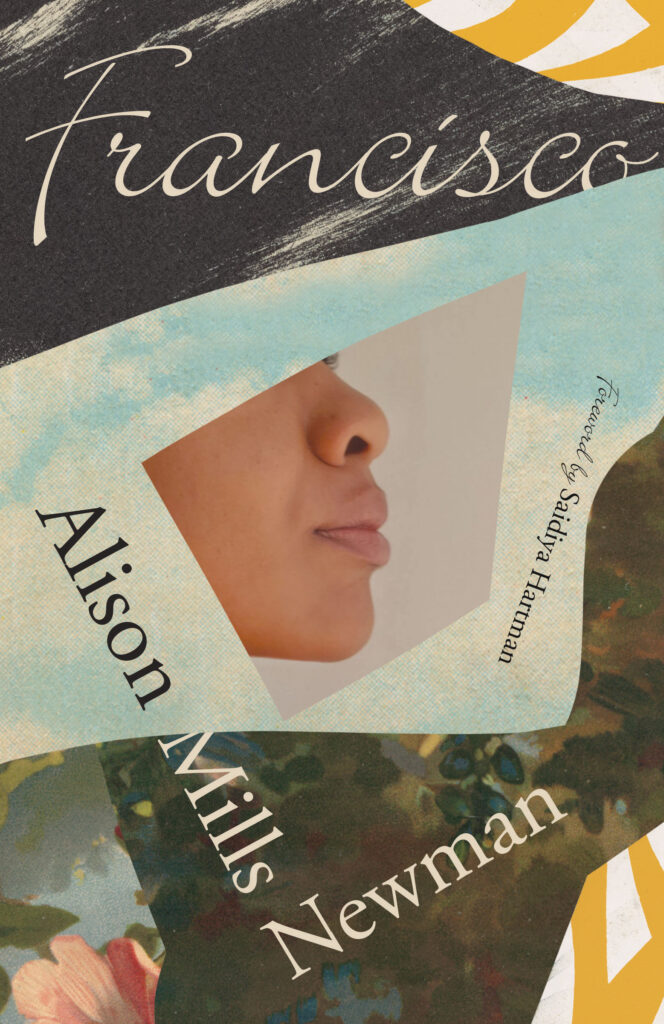

Alison Mills Newman’s Francisco, an autobiographical novel chronicling the young actress’ days in Hollywood and the 1970’s Black Arts movement, was first published in 1974. After years out-of-print, having fallen into relative obscurity, it arrives for contemporary readers as a re-release from New Directions with a foreword by Saidiya Hartman, forthcoming in 2023. Francisco chronicles its protagonist– an unnamed facsimile of Newman herself– drifting from day to day through California in the 1970s, demarcating time with a colloquial “anyways” addressed to the reader as she goes between San Francisco and Los Angeles after rejecting an early career in acting. Her language is flooded with the vernacular, all lower-case and typically taking on a familiar, conversational tone with the reader that makes her all the more charming. At once linear and fragmented through circuitous tangents about quotidian details, the protagonist’s narrative coalesces around one central figure: Francisco, an aspiring filmmaker from whom the novel takes its name. As Saidiya Hartman notes in her foreword, the novel “reads like a series of journal entries about the narrator’s infatuation and love affair with Francisco.”

But if Francisco is a series of journal entries, then it is a journal that knows it is being read with acute hyper awareness. The narrator writes to the reader, always cognizant of the culture she’s in, the scenes she enters, the connotations attached to every one of her movements. As much as the narrator drifts, she never relinquishes careful control over herself and others as subjects of sociocultural perception. Upon arriving at a party, she notices the “white women who were actin like they though janis joplin would act maybe,” keying us into not only the racialized imitative object– Janis Joplin– but to the flimsy nature of the performance itself, which hinges on how these women think Janis Joplin acts. The narrator utilizes the novel’s private extra-diegetic space to offer her own analysis of James Brown, college education, Hollywood, and social revolution and blurring together the personal and the political into a single, undulating meditation.

Through the narrator’s colloquial tone and fragmented structure emerges a dual narrative, at once a sweeping portrait of black culture in the 1970’s and a more personal, intimate tale of bohemian love between artist and muse, girl and boy, “great man and girl,” as the narrator describes it– and, ultimately, love for another and love for oneself as a black woman. The two intertwine, enmeshed, as an exploration of what it means to search for beauty and liberation.

— Sasha Starovoitov

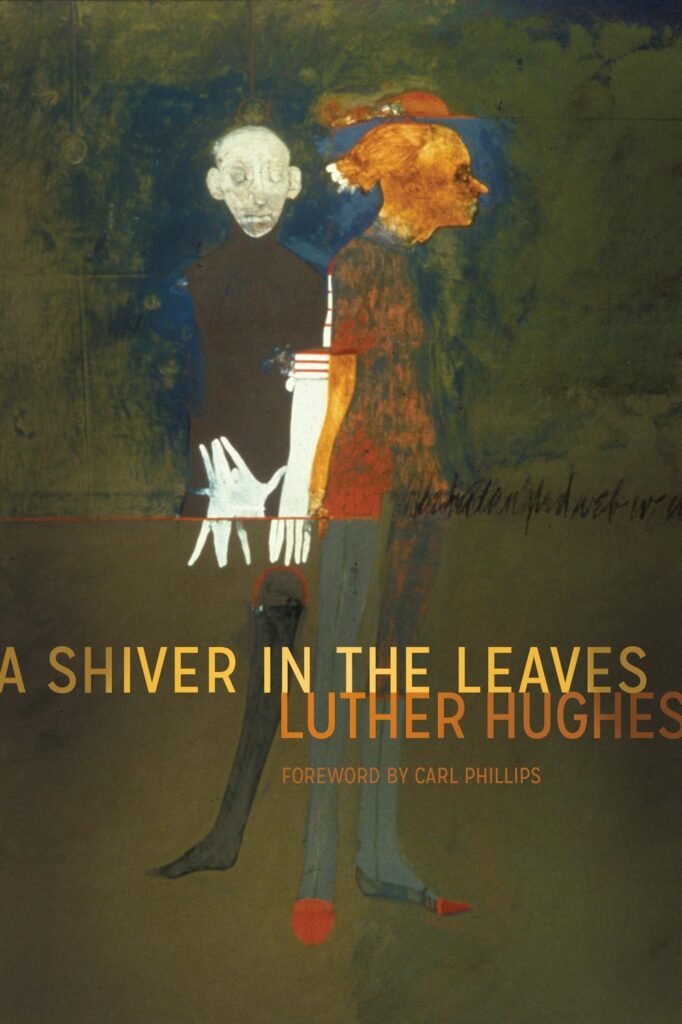

Crows swirl and gather in Luther Hughes’ A Shiver in the Leaves. As death-omens and figures of blackness, the birds flit through poems that sway with the tenderest desire and still with mourning. This debut collection from the Seattle-based poet memorializes black boys killed by police and black boys and men who were recent victims of anti-gay hate crimes (Tamir Rice, Giovanni Melton, Dwone Anderson-Young, and Ahmed Said among others). Against the pervasiveness of racist and homophobic violence, the poems in this collection ask if the spaces of healing and intimacy provided by queer domesticity can serve as a sort of refuge from the world. I think, in particular, of the poems “When Struck by Night” and “Making the Bed,” which appear one after another partway through the book, the former singing, “Everywhere there you are / with your eyes a warless country.” Just as attentively as they paint the soothing weightiness of this love, Hughes’ poems elegize the dead they name and consider the futility of such a project: “it is misleading / to sing in the presence of death.” Still, every poem-approaching-hymn of the collection may ask, what else is one to do?

Read these poems plucked from the trembling auras of sex and death; sway some time in their final quietness.

— Yeukai Zimbwa