When I first opened Ghost Forest by Pik-Shuen Fung, I sat alone in my room, one among the last

stragglers of those yet to vacate campus for the winter holidays. I finished it, hours later, still alone, curled

up in a puddle of my own tears. Fung’s slim novel of vignettes belies a devastating grief, one that follows

a family across the borders of estrangement and migration.

Ghost Forest follows the story of a young narrator’s relationship with her family after they

immigrate to Vancouver before the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the

People’s Republic of China. The narrator’s family stays in Canada while her father returns to Hong Kong

for work, creating what’s known as an astronaut family: family units living across different countries.

Space isn’t the only thing that separates the narrator from her father, however; throughout the novel, we

learn that he is frequently cold and disparaging despite her efforts to please him. He criticizes her 写意

ink paintings, admonishes her for not greeting him, and denigrates her college admissions (“Both are

good, but neither one is Harvard”). The narrator documents her growing distance from her father in

quotidian yet heartbreaking exchanges:

“The World Cup is starting in a few minutes, my dad said.

I imagined him standing on the other side of the door, facing me. Maybe he

would be looking at his feet.

I don’t feel like watching it anymore, I said.

I listened to his footsteps padding away.”

However, Fung pays careful attention to not portray the narrator’s father as a frigid antagonist. Small,

precious moments of the narrator’s love for her father add depth and complexity to their relationship. The

narrator’s grief after her father’s funeral, then, is doubly devastating: a loss that never quite unravels

completely.

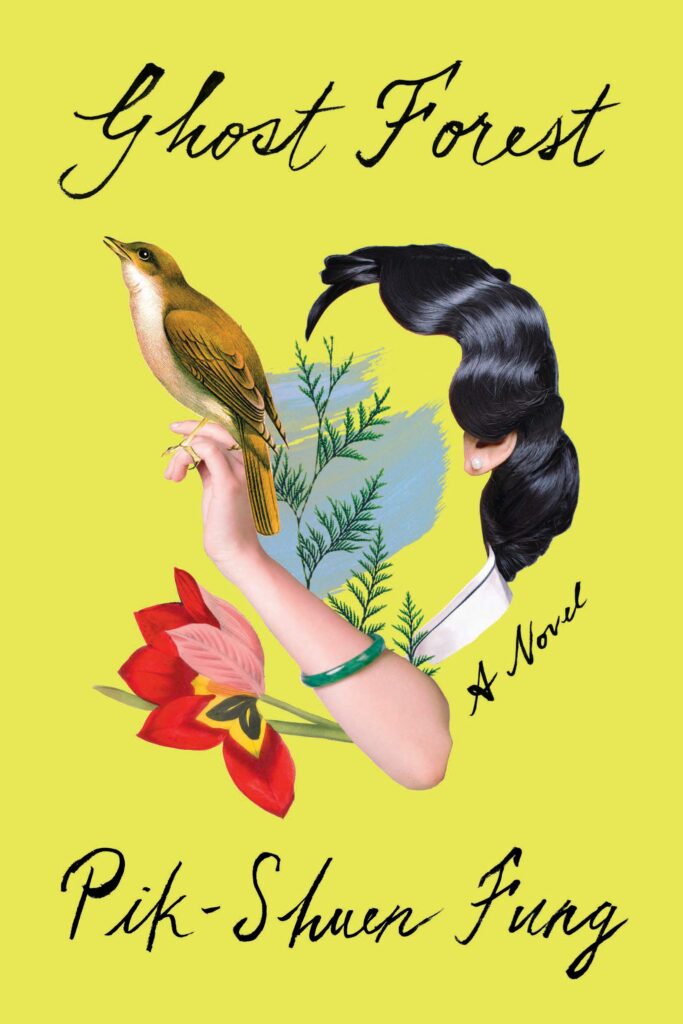

Fung approaches this loss non-linearly: the first story in the novel is the narrator’s

acknowledgement of her father’s death. The narrator recalls, “Twenty-one days after my dad died, a bird

perched on the railing of my balcony. It was brown. It stayed there for a long time. Hi Dad, I said. Thanks

for checking up on me.” Fung switches between perspectives, speaking from the narrator’s grandmother

or mother at times, piecing together a project whose very nature is to remain unfinished – Ghost Forest

reminds its reader in its brevity that for every story told, there are a million more left unsaid. Fung’s tight

prose and succinct details encourage the reader to fill in these missing pieces – whether with their own

memories or beyond, Fung provides room for the reader to navigate their own grief through her work.

For me, I found Fung’s blank space and concision to be the most poignant part of her novel. She

moves from memory to dream in just a few lines, emphasizing that her narration may not always be

reliable with what remains unsaid, unobserved – but that’s not the important part. Whether or not the

narrator’s father means it when he says “I love you” in English remains a mystery that Fung accepts in her

writing. What matters, Fung tells us, is what we remember:

“There is a memory I can revisit only in pieces.

I am standing in the hospital.

My dad is sitting up in his bed.Somehow, no one else is in the room.

There is a square of yellow sunlight on the floor, a small suitcase by my feet.

Outside, a taxi is waiting.

In this life, my dad says.

His voice cracks. He turns his face away from me.

In this life, he says, it is one of my greatest fortunes that I was blessed with

two daughters.”

–Ari X