Mid-September, I attended an exposition of local and regional experiments in text and sound hosted by Opus 40, an upstate museum and sculpture park located in Saugerties, New York. Verbatim (the name of the event) entailed a day’s worth of performances held between an indoor reading room and an outdoor stage space backdropped and canopied by deciduous trees. Opus 40 is also the name of the on-site earthwork sculpture hand-sculpted by one Henry Fite (an artist with whom I was unfamiliar before visiting) in the middle of the twentieth century. Between performances, I wandered around the ramps, platforms, and steps cut from stone that make up the sculpture, which struck me as an expansive human-made facet of its woodsy environment more than anything else. The behemoth work was toiled over by Fite for nearly four decades, reaching its de facto completion in 1976 when the artist, while at work on the project, slipped and fell to his death.

A couple dozen regional publishing presses had tables at the event with books for sale, including Litmus Press, Station Hill Press, and Black Sun Lit, among others. Many displayed books by authors who would be reading as part of the day’s program. It was at the table for 1080 Press––a small, Kingston, NY based publisher with a radical, resolutely DIY publishing model––that I picked up a copy of Tilghman Alexander Goldsborough’s THE WESTERN IS A SPEECH ACT. RUN TIME APPROX 20 MIN for a suggested donation of $10 ($5 venmoed to the author, $5 venmoed to the largely donation-driven press).

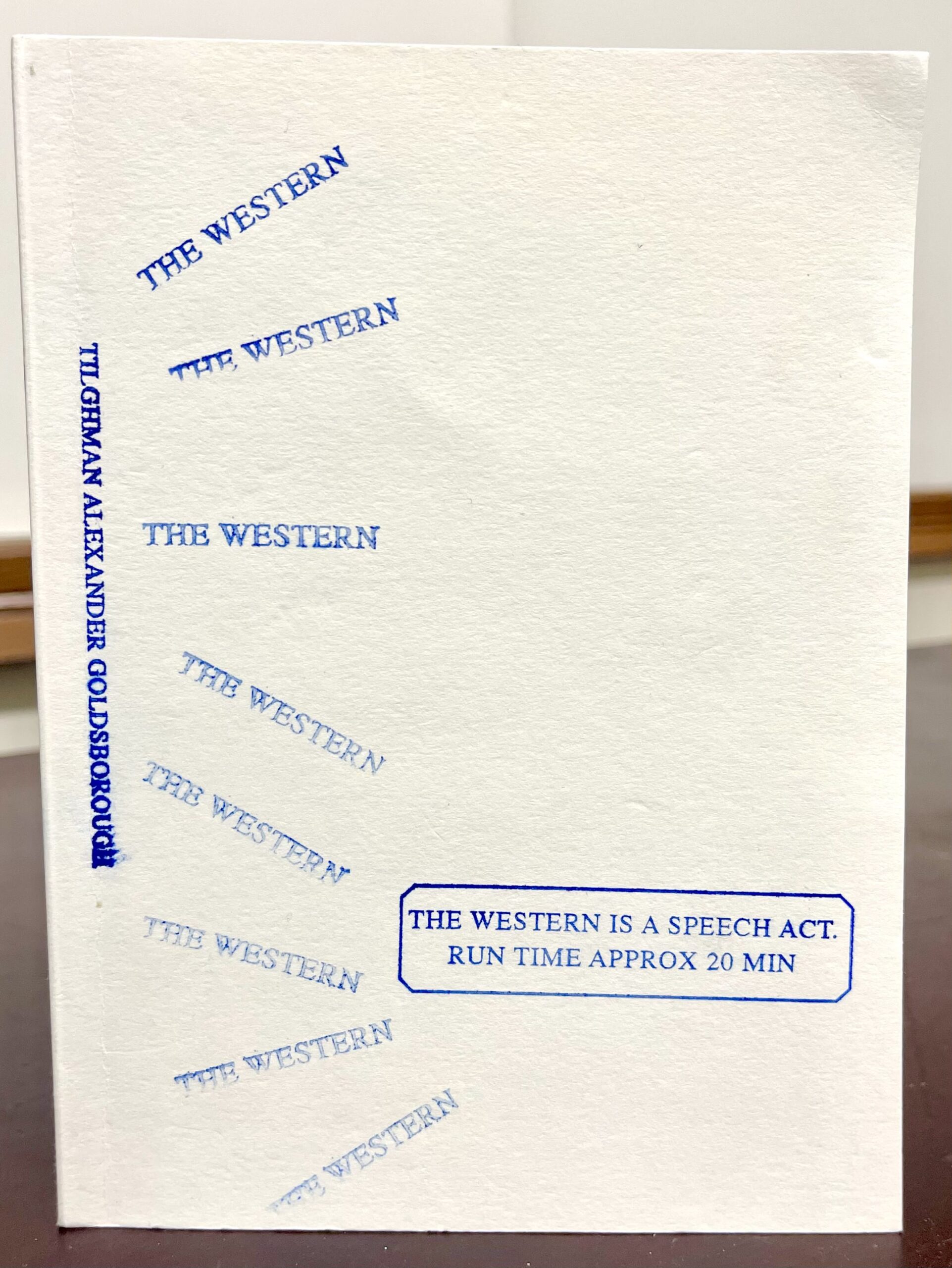

The volume came sheathed in a plastic slip that also contained a thank you card from the press and a quarter-folded essay that Goldsborough had written for the July 2022 installment of 1080’s author-written, paper-only newsletter series. Laid out on the table at the expo, copies of Goldsborough’s book had slightly different cover designs composed of various arrangements of the same components: three dark blue stamps reading the author’s name, the poetry book’s title, and “the western.” On the copy that I selected, “the western” appears several times along the left hand side of the cover, variously slanted.

I didn’t sit down to read THE WESTERN until late September, some weeks after Verbatim. What I had found most alluring while flipping through were the pages of dark blue lines drifting in white space––poems or poetic inscriptions that felt uncontained. That and the particularities of Goldsborough’s punctuation throughout the work. From the first poem, LINGUINE NINETEEN:

{& yet,} my greatest folly is that I continue 2B an American ::

{ [just] another dude out on the ranch :: }

Brackets and colons arrange the poem as though its content were coded instructions, language directing or put in service of computational tasks. Active as means to an extra-linguistic end. In this sense, the poem evokes a titular concern of the work––a concern with language’s ability to act and perform in social worlds––at the level of grammar.

{ [just] another dude out on the ranch :: }

Everything about the tone of the line dissembles.

[just] another dude

Seemingly innocuous. The image of this man “covered in grime, out of doors / sporten soiled dungarees & dirty boots / smellen like hot soil & cold piss.” But really embodying some epitome of (US)Americanness–– the same (US)Americanness of the 19th century wild west, as imagined and glorified by that genre of settler fantasy backlighting Goldsborough’s work. Great plains, outlaws, and sheriffs; cowboys, “Indians,” and masculine heroism. Goldsborough’s work seems cognizant of how the frontiers of US empire have exceeded Manifest Destiny’s visions of the Pacific coast ever since. What might be read as the computational grammar of some of the book’s poems corroborates recurrent depictions of life in the cybernetic fold: “recently I been glitchen”; “Got me stuck in the staticky present”; “Slurping green slop fuel 2 labor in the screen”; “nappy nodes weaving fabric of reality.” Given Goldsborough’s concern with empire, these considerations of life in the age of the digital arrive uncleaved from the colonial logics of the exploitation of labor and land that makes digital technologies possible. I think specifically about mineral extraction in the Congo.

{& yet,} my greatest folly is that I continue 2B an American ::

By Goldsborough’s estimation, some version of life in the herenow of a modern US city is characterized by gluttony and a kind of spiritual drift. We see the speaker of the poems caught between an overarching search for “salvation :: / A religious type ecstasy” and the nighttime pursuit of “new novel euphoria :: / 2 contrast hectic cacophony.” Glut, greed, and decadence materialize in the figures of food and eating that form a central motif of the book. These figures are severally resonant: sometimes expressing the tedium of endless consumption, sometimes rendering the absurdity of the hyperspecificity of needs manufactured by twenty-first century capitalism. At other times they mark the movement of time within the book’s flow of transmissions, a flow in which “days slip by in a kind-of fugue” and a sense not so much of meaning as of coherence seems to evade the speaker. Of course, the stakes of coherence are legibility and, from one vantage, success for the poet who may in the end just be looking at “The World, –– / disappointed , / tryna turn [it] into sth [it] aint , ––.”

About halfway through the book, there’s a reprise (if you will) of the opening poem entitled “LINGUINE NINETEEN (CITY CENTER).” In this poem, a vaguely located “corrugated ground” seems to represent “a lasting ordered pattern / a glimpse of Eternity ®” ––ideals that speak to canonical exaltations of the kind of beauty found in or achieved through poetic form and longevity (à la Keats). In some sense, these are ideals that empire and capital share with this kind of aesthetics. Violent state-forms imposed on indigenous lands by settler nations; dreams of endless economic growth and accumulation. Perhaps Goldsborogh’s formal vagaries resist a world-defining logic of ceaseless exploitation and dispossession just as much as (in the same instance that) they resist models of calculated poetic form. In addition to the literary resistance (if you will) enacted by the work, anarchic visions of revolution emerge: “Think abt [it] honestly for a moment :: // most proper response equals eruption of civ ending ultraviolence / [carried out collectively or in [autonomous] cells / w them currently known-as kin / bound by bonds of bifurcated sentience.” Yes.

One particular history of dispossession that THE WESTERN thinks through is the history of the middle passage and enslavement in the Americas. Goldsborough’s appropriately bleak portrait of neoliberal multiculturalism and the cosmopolitan American dream attests to this:

an indiscriminate progressive ,/, beat’n All [w/o prejudice] ::

every fortune seeker across the greyscale /

no longer just (the) maroons

patiently waiting , lost & looking for the eye of Aten

long-lashed n winking in the trees ::

ain’t been seen since,,crews of babtous swarmed over the horizon

2 beat black Africans till they became American

scenes now recounted as distant childish villainy ,––

as necessary labor pains

Following 80 day gestation /

brewing belowdecks in rat-filth human stink

The afterbirth of this history of subjection to violence, labor exploitation, and social death takes shape on multiple scales. At the scale of institutionalized anti-Black racism, the speaker pinpoints a structural position of “feeling less Free & more not-enslaved.” On a more affective scale, the scale of individual and collective grief, the speaker expresses a sense of [cultural / genealogical / familial] loss, both in explicit reflections on diasporic self-seeking (“feel disconnected from my own history ,–– / hollowed out , ”) and in imaginative invocations of ancestors. In the same poem in which the line “feeling less Free & more not-enslaved” appears, the poet writes, “yearning 4 a desert dance 2 call on the ancestors :: / elders arriving in electronic trance , walking // loose hipped ,, loose lipped // spilling secrets that feel familiar.” Elsewhere, in the dream-vision-like poem “WESTERN SKETCHES (SINKO AGOGO),” the speaker conjures a scene in what is perhaps an oneiric Ethiopia (“clay coloured village thousand miles from addis”) where a spiritual revelation takes place, for which the speaker sports (with text-speak glee) “my v own religious red headdress,” (re)connected to a sense of fancied indigeneity, at least in the space of the dream. In both moments, the speaker incites the literary imagination to traverse distances and absences wrought by colonial history, marking another extent of the book’s insurgency.

Sitting with this particular dimension of THE WESTERN––Goldsborough’s reflections on diasporic self-seeking and dreams of (re)convening with ancestors––returns me to the sculpture park at/of Opus 40. At one point in my wandering, I remember descending stone-cut steps while holding lightly to the stone-cut wall of a circular platform that the steps wrapped around. For a moment, I got the sense that I was walking through a corridor, or a larger stone enclosure, though Fite’s sculpture is not encompassed by walls. By some bizarre figment of diasporic reverie, I saw myself there again, within the walls of a stone-built structure laid some ways south of the Zambezi, tracing my hand along an enclosing, mortarless wall of stone; there in a place I had never visited, that had been uninhabited––static in its state of ruin––since the 15th century…

{& yet,} my greatest folly

***

Secured from threat of wind by a slate-colored rock, a humble piece of graph paper with printed text lay on 1080 press’ table at the expo in Saugerties, displayed beside books, previous newsletters, and a mailing list sign-up sheet. The title of the page read, in all drop cap letters, “TEN PREFATORY NOTES FOR GREENSKEEPERS.” The penultimate note reminds and advises:

9. Words and phrases accumulate history, antagonizing the writerly impulse to reimagine language

- Composing to facilitate decomposition brings writing in line with language’s capacity to organically reimagine itself

In THE WESTERN IS A SPEECH ACT. RUN TIME APPROX 20 MIN, Tilghman Alexander Goldsborough composes to facilitate decomposition, setting a place for language, reader in tow, to reimagine itself, to become the space and act of reimagination. From out of the dark:

[,,,, a vision ::

the future arrives ::

barefoot & confident /

fondue oozing a triumphant grin

— Yeukai Zimbwa