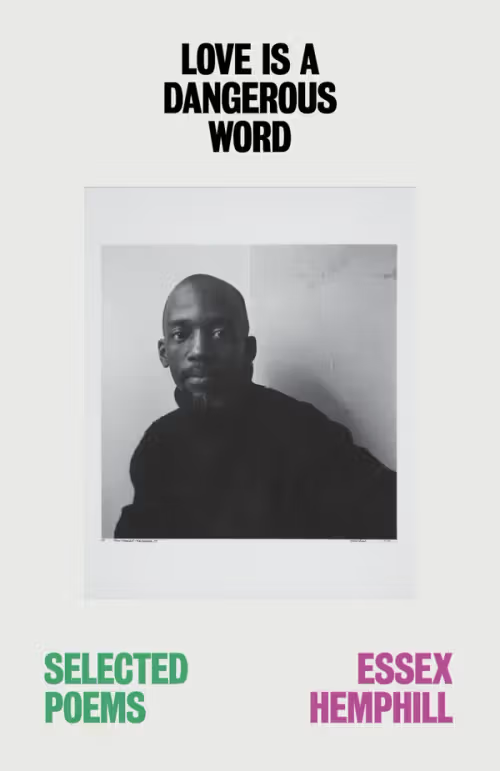

Love is a Dangerous Word / Essex Hemphill / New Directions Publishing, March 4th, 2025 – $16.95 (paperback)

The work of an artist, a poet, a performer and an activist is revived in Love is a Dangerous Word, the posthumous anthology of Essex Hemphill’s poems. Essex Hemphill rose to fame in Washington DC’s art scene in the 1980s. His artistic work, which focused on the experiences of Black Americans and the sufferings of the queer community during AIDS, resonated with readers beyond DC and across America. Forty years after his death, Hemphill’s writing returns to bookstore shelves, and even now his words feel immediate and important. Hemphill’s poetry has become timelessly influential in the queer, Black poetic canon and valuable as a historical fragment of the HIV/AIDS crisis in America. Love is a Dangerous Word finds tenderness in the space between Hemphill’s growing grief around death and his eager exuberance for living. Though the poetry is at times elegiac, memorializing individual people in Hemphill’s own circles and all the American art lost to AIDS, it still manages to laugh at itself: its intrinsic pain is cut by humor, with escapades into cheeky queer landscapes in poems like “Invitations All Around.”

To crave sex with the dead, to be voracious in a time of AIDS, to masturbate and discuss it, to objectify one’s genitals purely for pleasure. In reading Hemphill’s work we do not ask the poet to take responsibility for his words and desires. We soak in them instead, learning how they resonate with our own thoughts and allowing his honesty to soften the edges of our judgement. My own breath bated as I read “Heavy Breathing,” a poem like a dark and twisting love affair with one’s own longing. Hemphill’s poetry is both raw and restrained. It makes readers recoil in surprise and just as quickly grin at the speaker’s sharp audaciousness. In “Visiting Hours” Hemphill puts to words the hilariously brazen thoughts of a Black security guard asked to protect European artwork:

“And if I ever go off,

you’d better look out, Mona Lisa.

I’ll run through this gallery

with a can of red enamel paint

and spray everything in sight

like a cat in heat.”

I was moved by the introduction of Robert Reid-Pharr, who spoke of seeing Hemphill in decline from illness, and in their final goodbyes understanding, “just how thin their words are.” In the slowly dying man across from him, Reid-Pharr saw a deep well of love and he saw himself — a sight too terrifying to speak of. Perhaps that is why we write: to exhale those sensations not yet speakable, but too present to deny. To bear witness to our communities in the thick heat of experience, of loss and discovery. “Take care of your blessings!” Hemphill would reportedly shout to friends as he bid his farewells. Though his life was short, those close to Hemphill often note his ceaseless effort at spreading love. And though love is indeed complicated and full of anguish, Hemphill did not hold back. In his writing, no word is avoided, none deemed too dangerous to proclaim.

“I’m an oversexed well-hung

Black Queen

influenced

by phrases like

“I am the love that dare not

speak its name.”’

Black Queen

– Silas Silverman-Stoloff