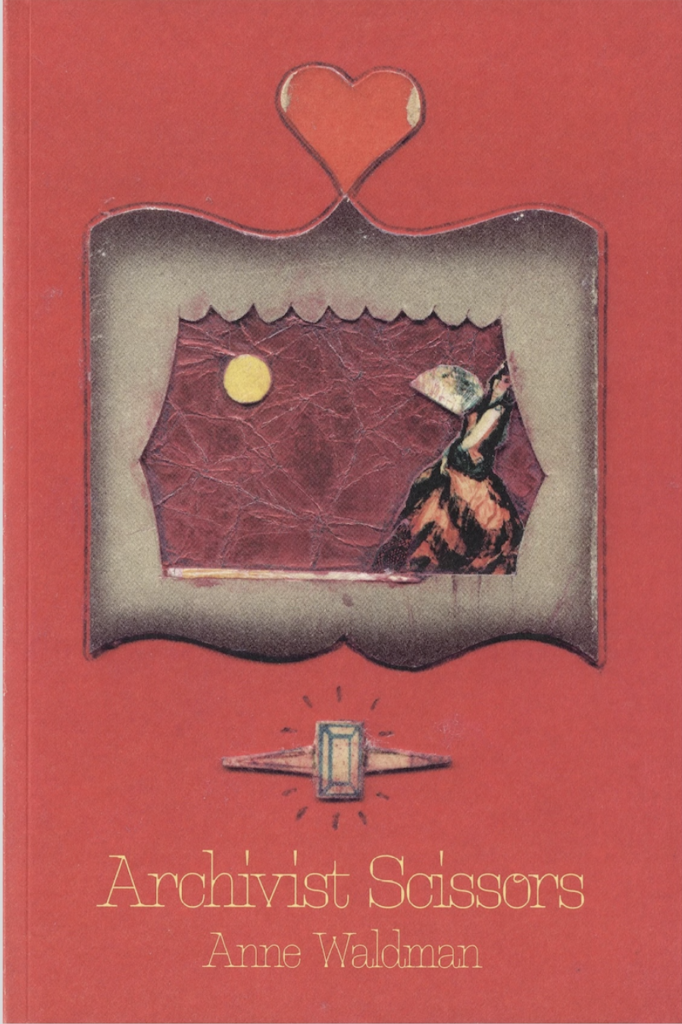

Archivist Scissors / Anne Waldman / Staircase Books, April 29th, 2025 – $20 (paperback)

The first and only time I had met Anne Waldman was after a reading at DADA, one of my favorite bars in the city. I had stumbled in on a wintertime Tuesday night not fully knowing who she was, but after a clear Google search made her connection to the Beat Generation clear to me, I was intrigued. I ended up spending the whole of her reading at the edge of my seat, waiting to catch the intonation with which she delivers the next word. I drew comparisons between her and other Beat poet readings I had heard in the past, but more importantly, I could immediately tell that these were poems meant to be spoken — that their cadence was engineered for the audible form.

For this reason, as I first flipped the pages of her new book Archivist Scissors six months later, I felt somewhat lost. Full of parentheticals, slashes, and abruptly-ending sentence fragments that read like loose, floating thoughts, these poems seemed to me allergic to being read aloud. Yet, I sensed an intentionality in this departure — a change in inherent purpose. The “Archivist” in the title bolsters the idea of this departure; Anne Waldman is writing to keep a record rather than a rhythm.

While Archivist Scissors certainly reads as Waldman’s attempt to piece together a tapestry of her corner of the literary world, the project extends far past her life and lens. The crux of the book lies in the question: how do we remember others? The poem “Assignment” grapples with Anne Waldman’s attempt to preserve the memory of Joe Brainard, author of the experimental memoir I Remember. In numbered steps, Anne Waldman talks the reader (and herself) through what to say in this interview, where the interview should be set, what quotes and memories to include, how to describe her relationship with him, what order, essentially, her brush strokes should follow so that the portrait she paints of Brainard is proper:

3.Then talk about the first time you met Joe, what do you remember about him, how he looked, how he spoke, his demeanor, how you became friends, what it was like to be friends with him. For this part it would be great if you could start your sentences with “I remember.”

There is a charming element of meta in this poem also. By passing forward her recollections of a writer whose work was deeply rooted in memory, Anne Waldman brings to light the recursive nature of the archive she forms — how we are, as Brainard was, all parts of the archive as much as we are its keepers.

As many things do, Archivist Scissors reminded me of Derrida’s last interview, in which he identified the “traves we leave behind,” whether “spoken or written,” as “never simply ours but already from the very beginning beyond us and out of our control”. He went so far as to say that these traces even “leave us and begin to act independently of us” — an interpretation that turns elements in the archive from objects into living beings. I sensed this same animation in Waldman’s work, with each memory transcending the bounds of the original beholder. Overall, I found this collection to be both a heartwarming tapestry and a sincere reflection on what it means to remember, let alone record.

– Al Sherbatov