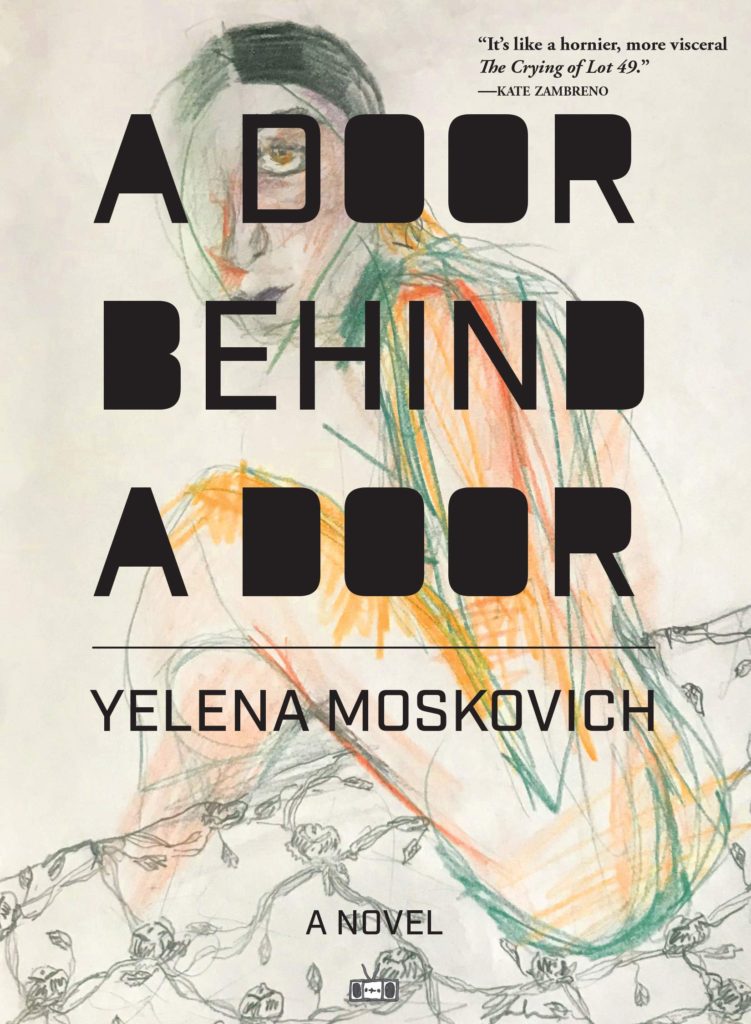

A Door Behind a Door by Yelena Moskovich

Yelena Moskovich’s A Door Behind a Door may be disorienting to a reader who desires a clean narrative—one in which paragraphs follow patterns and create a linear portrait to follow, allowing the reader the comfort of settling into the novel. Moskovich refuses such comfort, bending tradition to build a world that leaves the reader between dream and reality.

A Door Behind a Door is comprised of fragments and vignettes that chronicle the lives of ex-Soviet immigrants in Milwaukee, a setting reminiscent of Moskovich’s own childhood growing up in Wisconsin after her family left the Soviet Union when Moskovich was seven. Moskovich’s plurality of style and identity is not just woven into A Door Behind a Door; it is the novel. Without its surreal, drifting style, the novel would falter in Moskovich’s uncompromising portrait of the Eastern European imagination in a distinctly American context.

The novel’s first moments begin with its central character, Olga, living in the shadow of a recent murder. Nikolai, a boy in Olga’s apartment, has killed an elderly woman in their apartment building. For an American reader, the scene may simply register as an act of random, criminal violence. But to anyone familiar with the insularity of Soviet apartments—the tight quarters, the gossip that flows through the building, the desolate, dark stairways—the act is almost natural, a conceivable reaction to the claustrophobia of Soviet khrushchyovkas. From there, the novel follows Olga’s immigration to the United States with her family, including her brother Moshe. In a few pages, Olga grows up, Nikolai returns, and the novel descends into its surreal primary plot: the disappearance of Olga’s brother Moshe and Olga’s subsequent search for him. Olga finds a tangled criminal scheme housed in a diner, riffing a historical staple of Americana landscapes. The vignettes often break: Olga expresses her love for her girlfriend (a rare depiction of Russian queerness in immigrant communities and one that Moskovich routinely incorporates into her fiction); secondary characters give readers a disturbing look into the motives behind criminal, physical, and emotional violence; and pages of single sentences in an enlarged font interrupt the novel in a style reminiscent of Donald Barthelme’s postmodern experimentation.

Moskovich, with brazen language, weaves together a novel filled with polarities. She plays, twists, and turns, always contrasting the brutal with the beautiful in her vignettes and leaning into the oddities of the English language (perhaps, in part, influenced by her own knowledge of several languages). In a literary culture obsessed with realism, Moskovich presents a refreshing take on the absurd and avant-garde.

–Sasha Starovoitov