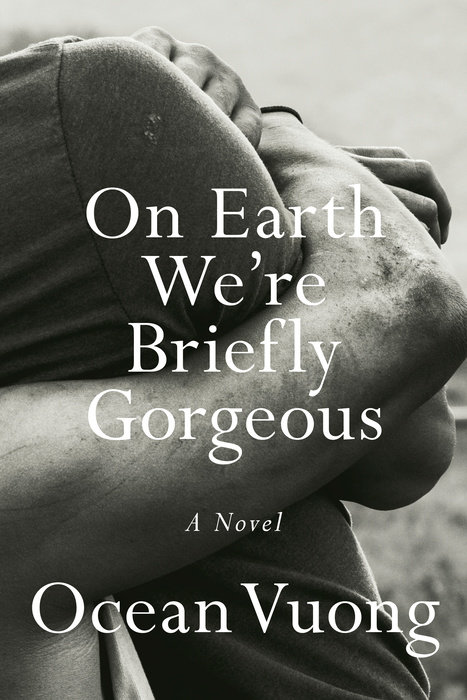

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

It is a pleasure to read a sentence that makes language new; it is a revelation to read a book full of such sentences. Ocean Vuong’s debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous creates a language of longing. The novel is framed as a letter from the protagonist, Little Dog, to his mother, who cannot read or write. The letter explores the notion of inherited trauma as Little Dog suffers the after-effects of the war in Vietnam—a war that has broken and reshaped his mother and grandmother’s lives.

Little Dog develops traumas of his own. The early portions of the book are devoted to the physical abuse that Little Dog experiences as a child. As a teenager and young adult, Little Dog is embroiled in a tumultuous and drug-filled romance with a local boy, and these sections are violent as well. These scenes are neither gruesome nor gratuitous, although they are difficult to read. Vuong’s language is beautiful, but not at the expense of raw feeling—raw as in fresh from the cut, raw like a wound that has been poked and prodded and examined many times over. Which is to say that Vuong’s prose is a contradiction—both thoughtful and instinctive, carefully considered and straight from the gut.

The novel’s intensity does not wane as the story progresses, it simply transforms. Vuong applies a poet’s eye to the work, modifying the novel’s language, syntax, and formal structure to suit the particularities of each trauma. No two griefs are the same – he seems to say. The result is a book that doesn’t feel, or read, like anything else.

–Sofia Montrone

Can you say the same thing in radically different ways? This is the question Lydia Davis explicitly asks in her essay, “A Beloved Duck Gets Cooked: Forms and Influences I,” featured in her new collection, Essays One. It is also a question she confronts throughout the collection as a whole. In Essays One, Davis examines the question of translation, when you translate something, are you saying the same thing? She explores the multiplicity of form by delving into the short story and how it can take on the form of a questionnaire or a language lesson and continue to be a narrative. Davis does not confine herself to the written form, either. She explores the works of visual artists such as Joan Mitchell, Joseph Cornell, and early twentieth century photographs in sections she titles “Visual Artists,” sprinkled throughout the book.

The magic of Essays One is that the form itself answers Davis’s question of the ability for something to be the same in radically different ways. The book is both a collection of critical essays and personal narrative. The essays are stories about stories and how they are formed, meditations on Davis’s own evolution as a story writer, love-letters to the act of writing and personal style. Essays One also a critical approach to the styles and writings of the authors who influenced Davis. In “A Beloved Duck Gets Cooked,” Davis writes about a poem by Anselm Hollo that reads “i shouldn’t have started these red wool mittens. / they’re done now, / but my life is over.” In these three short lines, Davis explains that she sees something new with each reading. Though Essays One is 501 pages instead of three lines, I too, am delighted to find something I have never seen before each time I sit down with it.

-Elizabeth Meyer