The Close Reading Series invites our board editors to write about a favorite piece from our Spring 2020 issue. These readings are not intended to be definitive interpretations; when we read, we bring with us our own histories, experiences, and references, all of which guide our relationship to the work before us. It is possible, even probable, that the meanings our editors found in these pieces will be different from your own, and perhaps even different from the authors’ intentions. We hope that these close readings will demonstrate what we loved about these pieces, and encourage you to find things to love about them as well.

This week, editor Spencer Grayson discusses “Newly, rendered, truly.”

What I love about Kelly Hoffer’s “Newly, rendered, truly” is that, despite its sensual imagery—the speaker “lay[s]” their “pleasure across / the bed” and imagines being “dropped into a pool of cooling / lust”—its words operate less as signifiers for emotions and experiences than as meanings unto themselves. To me, the poem does not describe a scene of pleasure so much as it glories in the strangeness of poetry: how a word or phrase can mean nothing and yet make perfect sense. It’s for that reason that I think the first four lines are the best of the poem. Every time I reread this piece, I focus especially on those lines, noticing the rounded sounds, the echoing vowels.

Then I notice the enjambments, especially “ready for the swoon to fool / me, dropped,” “pool of cooling / lust,” and “a flower spools / sweet things beside.” When I read these enjambments aloud, their digraphs extend beyond the breath I took to read the full line. I become more conscious of taking my next breath in the middle of the following line. The poem forces an awareness of its rendering. You can’t read it smoothly, can’t ignore irregular shifts in breath and images that resist clarity.

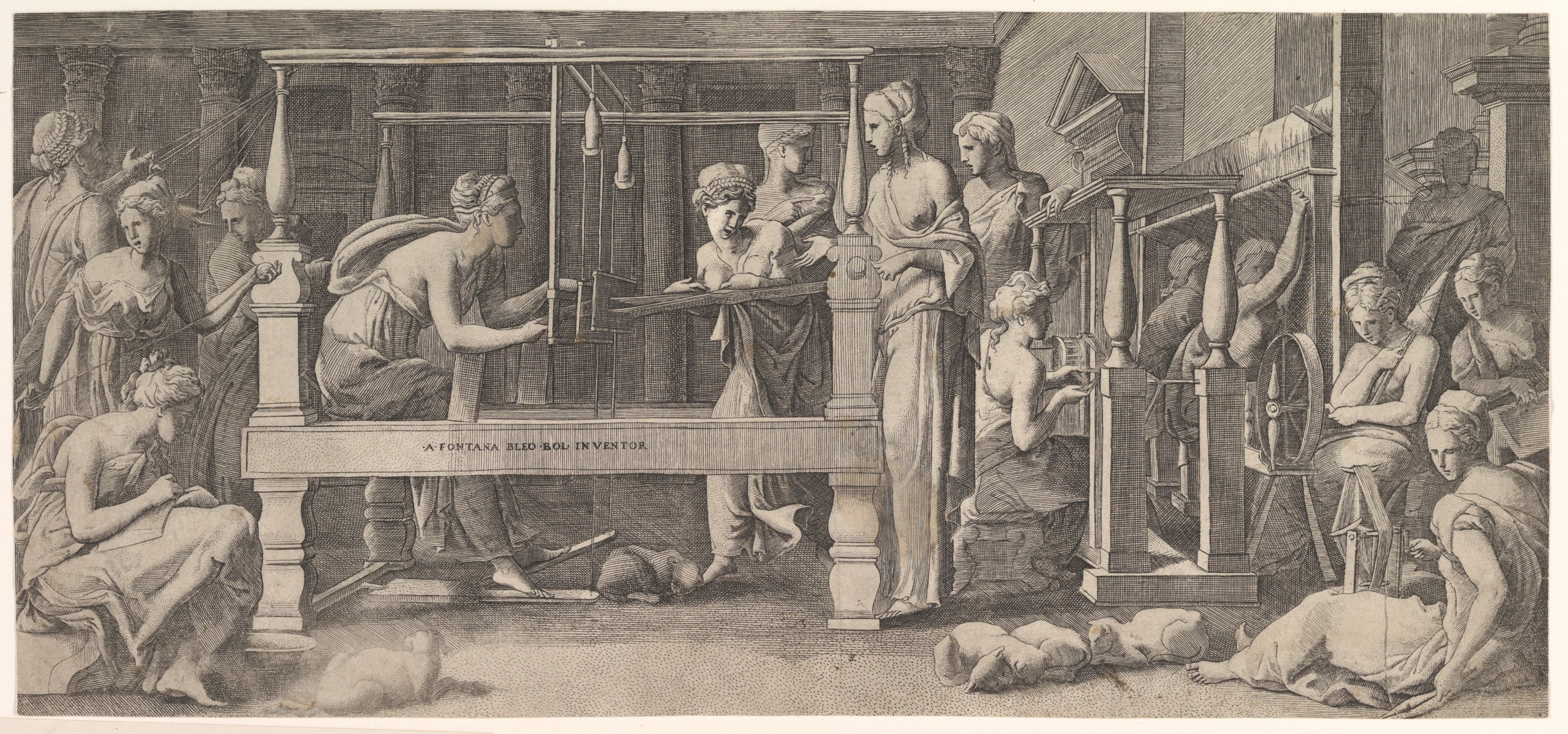

Towards the end of the poem, the speaker asks: “if I give you a phrase will you sup- / ply the subject.” It is possible to supply a subject by offering a “deeper meaning” of Hoffer’s poem. “Newly, rendered, truly” is arguably concerned with the acts of spinning and weaving, writing itself: the language is formed of organic material, flowers “spool[ing]” phrases like thread and “sentence[s] seamed with stitching / nectar.” But, in response to the speaker, I would suggest that a subject and/or metatextual reading is not necessary to find that deeper meaning. Every sound in “Newly, rendered, truly” gives pause, and I keep returning to experience them all over again.

Read more of our Spring Issue here.