Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind is a spellbinding love letter to nature. The collection, separated chronologically into four seasons, opens in the spring with a description of a groundhog on its haunches, stealing tomatoes from a backyard garden. Observing this quotidian scene with unmatched curiosity, the speaker compares herself to the animal, wondering, “Why am I not allowed delight?” From this query onward, Limón revels in the interconnectedness of nature and human experience. Depicting cockroaches, lindens, forsythias, horses, and hawks, she writes of loss, infertility, and cultural and familial legacy with stunning attention to detail.

The Hurting Kind is a balancing act of interiority and exteriority, minute daily occurrences and expansive natural scenes, human feelings and physical manifestations. The collection emphasizes the profundity of nature without human intervention. “Why can’t I just love the flower for being a flower?” Limón asks, calling into question the claims that humans place on nature. After much consumption and conquest, are humans even worthy of naming trees: wondrous, stately beings “shaking off the torrents of rain as if… simply making music”? Alongside these layers of external description, there is an exceptional depth and poignancy to the speaker’s internal world: “I will never be a mother,” the speaker proclaims in one poem which, at its surface, depicts horses on a hillside. In acknowledgement of “the hurting kind,” Limón recognizes painful emotion as just as natural and deeply rooted as trees, flowers, and groundhogs.

By the end of the collection, one feels at home in Limón’s writing, cozied in the familiar and meditative imagery, reluctant to leave. Because Limón’s poetic truths are tightly interlaced with natural descriptions and metaphor, simply reading The Hurting Kind is a delightful practice in self-reflection and in the very observational skills and attunement Limón exercises so beautifully.

–Neena Dzur

“Nuestros cuerpos “Our bodies

dos jaguares solares two solar jaguars

enfrentados en la noche faced off in the night

acabarán desgarrados end clawed up

en el alba total.” in the total dawn”

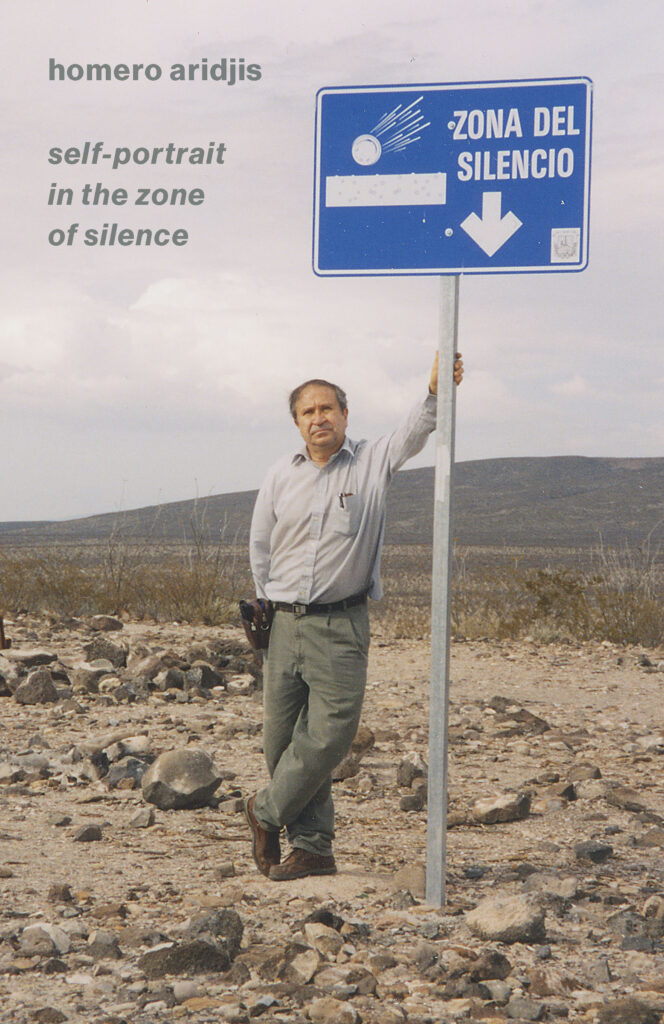

Homero de Aridjis’ Self Portrait in the Zone of Silence begins with “El Jaguar/ The Jaguar,” a powerful ode to the native Mexican symbol of strength and survival. The poem, composed of five parts, is a confrontation with death: the destruction of the jaguar provokes the reader to contend not only with the colonization of the Americas, but also with the poet’s own mortality. Aridjis, a native of Michoácan, Mexico, is renowned for his poetic legacy, as well as his environmental activism and his service as Mexican Ambassador, among other accomplishments. His new collection, forthcoming in February 2023, struck me as a culmination of this life’s work. The poems do not all explore environmental and national themes, but the encounters with the morbid and the ghostly are paired with distinctly Mexican images– between the volcano Popocatepetl and the Aztec goddess Coatlicue, Aridjis crosses the boundary of past and present in order to bring the land of the dead to that of the living.

While the poems are deeply Mexican, they are also intensely personal. The writer is very conscious of his influences, but the status of the book as a self portrait implies that the borders between Ardjis’ environment and self are fluid: he is as much himself as he is the jaguar and the mountain. In the last poem of the collection, “Autorretrato a los ochenta años/ Self Portrait at Age Eighty,” Aridjis reflects on mortality and the creative power of poetry in his life. For him, “being and making poetry are the same… Dust I shall be, but dust in love.” This embracement of death characterizes the collection as an intimate and moving journey to the beyond and unknowable, an exploration only accessible through the poet’s willingness to reach inside and bear himself forth.

–Gabrielle Pereira

Claire Schwartz’s Civil Service—courtesy of Graywolf Press this past August—opens with a request: “please, come in.” Soon after, the tall, gaunt outline of a milk carton hovers above Schwartz’s words, having grown in size from page to page from the book’s beginning. “Inside the milk carton: I,” she writes. “The town square, the threshold, the book. / The house, the host, the cell, the hormones, the history.” And she wonders aloud: “Is this a house or a cell?”

Civil Service is clearly (and self-consciously) the culmination of many years of what Fred Moten refers to as study (a “devotional, sacramental, anamonastic kind of intellectual practice”): Schwartz writes first and foremost as a reader, and the book wonders seriously and thoughtfully about state power, 21st century capitalism, race, sex, love, and even—maybe especially—metapoetics.

In reaching for Civil Service’s central conceit, it might be easy to think of the book as essentially parabolic. Many of the collection’s poems catalog the foibles of an almost comical procession of many of state power’s myrmidons: the Archivist’s sight is obscured by books; the Board Chair, repeating I hear you, silences a female colleague; the Intern, ignoring her family’s requests for money, tucks a penny under her tongue. Yet, after a faux-exegesis of her poem “Parable,” Schwartz offers a reminder of sorts: “Oh, the many ways to misread,” she writes. “Or that other risk, the greater one, and what you’d have to do with it—.”

Parables are, of course, didactic in nature. And Schwartz, capable of cutting deeply from the most vertiginous heights of abstraction, gives the feeling that, by the end of the book, hardly a stone has been left unturned. Yet, though Schwartz offers no shortage of steely epigrams and pithy turns of phrase on everything from confessional poetry to ownership, nothing about the book is closed or contained. “Poetry is a door without a house,” she writes. Later, she adds:

“A person can be with a word like they can be with a body:

Wash it.

Accompany it.

Be changed by its nearness.”

Civil Service is, if nothing else (although a lot more), a lot of words. May we treat it as such.

–Chase Bush-McLaughlin