“I need a volunteer. This is a choose your own adventure poem,” says Juliet Gelfman-Randazzo, self-proclaimed “Tall Spy” or so says her Instagram handle, followed by “unfortunately u can’t prove i’m not tall or a spy.” We’re in an era now where our Instagram bios are used to define us, I guess.

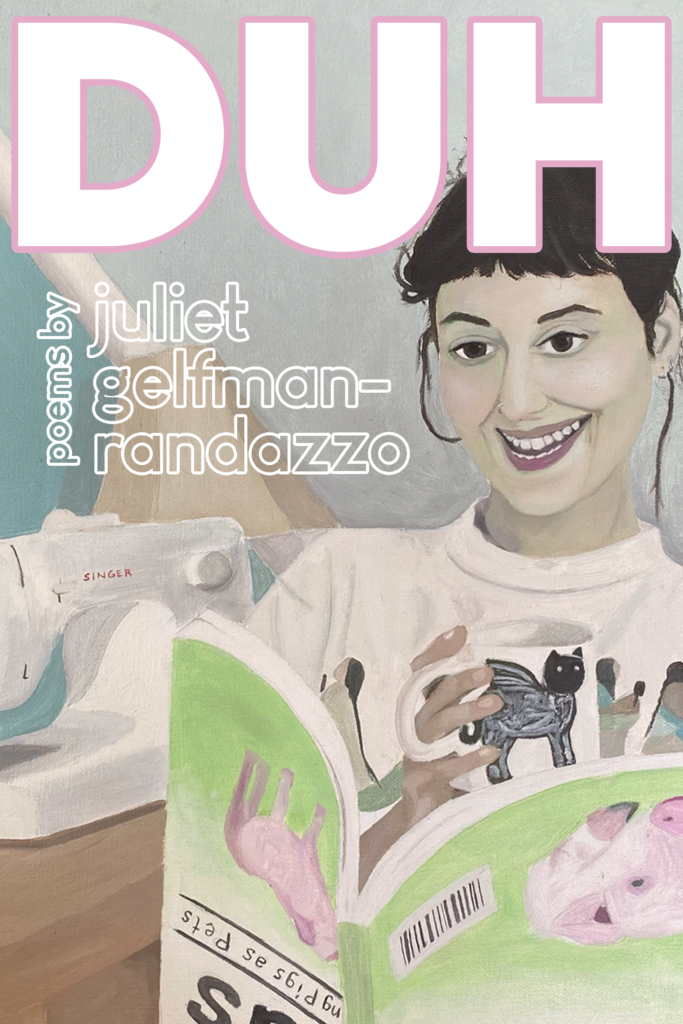

Gelfman-Randazzo is 5’8” (she tells us) and also a poet. And she’s reading from her latest chapbook, Duh, in the backyard of a small used bookstore in Prospect Heights. 13 minutes past the start time, my friend finds a fortune in his jacket pocket, “Listen these next few days to your friends to get the answers you seek.” 17 minutes past the start time, they bring out wine. 22 minutes past the start time, we begin.

Most of the people that make up the audience are doing just what the fortune foretold: listening to their friends. As it will be revealed through intimate introductions by the other three poets leading up to Gelfman-Randazzo, they’re a part of a poetry web strung together by pandemic Zoom-call workshops, self-confident DM’s, and poetry that, in the truest sense of the word, is contemporary (see: sonnets about queer sex).

Gelfman-Randazzo reads in the way every poet probably thinks they read: making everyone feel as if they’re the only one in the room. It’s a balancing act in pause: long enough between each line break to feel intimate, but not long enough to feel awkward.

And she needs a volunteer! My friend, Nat, is the lucky sacrifice. She’s found her volunteer and thus the reading can begin,“You are trying to sell something at the mall,” she starts, and later lays out our options, “to give them a free sample spritz of perfume and whisper, be the bee that buzzes its bodacious body into the lip of the flower, aching to soak in an aromatic shower, turn to page 2.” Or, “To offer to take their headshot, turn to page 3, glossily.”

When asking Nat what they thought of the event they said, “Well, all of the poets have hyphenated last names.” And what a better metaphor for Gelfman-Randazzo’s poetry! It’s skillful use of device mashed together with a line about simply taking a headshot. Or, later in the book, a poem titled “Do you believe in life after love,” interrogating our values, mashed together with the titular poem, “Duh.” You never know where you’re going next and when you get there, it’s a hyphenation of the last things you would expect.

We get to page 5 and Gelfman-Randazzo asks us again, “what do you do?” “To sell yourself short, turn to page 7. / To sell your soles, turn to page 9.”

If you didn’t get it from all the choice images that Duh conjured in my mind, or if you just want this review summarized because we live in an attention economy, some perfunctory remarks: Duh is profoundly human. Duh reminds us that being human is also embarrassing. But in Duh, we are “all made of rubber!” (“Pa-la-la-la”) so it doesn’t matter anyways. We “have no parts to pee or poop” and we’re all “having a blast!” No need to be embarrassed. Duh, features confessions, explorations in form, and a whole lot of Gelfman-Randazzo’s unfiltered musings on life.

It’s a hard time to be funny and also be a good writer. The study of contemporary poetry often demands question and answer all in one. Yes, you talk about capitalism, where is your solution? Gelfman-Randazzo, instead, writes, “I don’t want to raise a child in a world where beer is cheaper than gas and you can buy bougie water that costs more than both” (“I don’t want to raise a child in a world without sidewalks”). She doesn’t have the answer to this problem, but she does “want to rewrite this so a child could play on it, swinging from line to line like monkey bars, and if they fell, they’d just get caught by a trampoline—the safest one ever, safer than one that’s been invented yet, so the worst thing that could happen is they’d bounce back to their feet and keep going.”

You can’t see the form of the poem, but I can. And Gelfman-Randazzo has constructed her one-two line stanzas in just that way: monkey bars to swing on and trampoline to catch us. Gelfman-Randazzo isn’t writing us the solution to the problem, she’s constructing it.

Duh is also distinctly imaginative. Polly pocket houses. Cake as a space to explore insecurities. Poems that edit themselves. Metaphor you wouldn’t think of on the first go, but once it’s said, it’s so right.

Gelfman-Randazzo concludes her reading. Hugs are dished out amongst the poets. I tuck the fortune cookie slip into my pocket and leave with more questions than answers: what is the meaning of this aptly timed fortune? What makes a good poem? How do I successfully achieve being funny?

But, to get the answers we seek, you need to experience Duh all yourself. Turn to page 1.

— Sophie Anderson